What the Russians did back then can’t be forgotten, but I have forgiven them

Download image

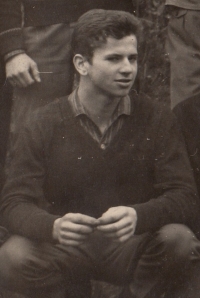

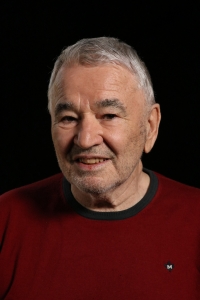

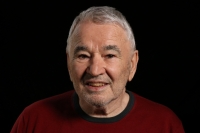

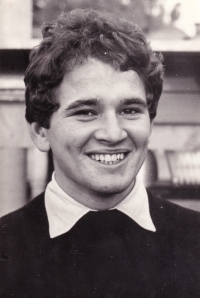

Petr Šída was born on 5 February 1944 in Lomnice nad Popelkou. After vocational school he worked as a wireman for Czechoslovak State Railways. He underwent compulsory military service in Martin and with a secret rocket detachment in Terezín. He later worked as a well-digger. He and one friend planned to emigrate to Canada. The events of 21 August 1968 had a fundamental impact on his life. He experienced the invasion of Warsaw Pact forces in a very direct way - Soviet soldiers shot him seven times in front of the town hall in Liberec. It took him more than two years to recover from his severe injuries. In the 1970s and 80s he worked in production jobs affiliated with the local agricultural cooperative. After the Velvet Revolution he and his brother Josef started doing business in hazardous waste disposal. In August 2014 he was awarded a Commemorative Medal of the City of Liberec for his selfless and courageous act on 21 August 1968, when despite his injuries he gave up his place in the ambulance in favour of the wounded youth Jindřich Kuliš. He retired in 2008. He lives in Liberec with his wife Alena.