The fate is a pseudonym of God’s Providence

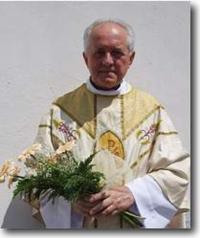

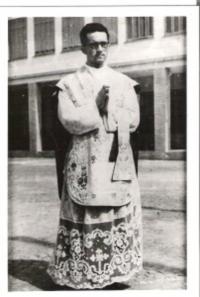

Štefan Šilhár was born on July 2, 1932 in Pezinok. When he was only four years old, his father died and his mother had to work very hard to be able to take care of three little children. After the elementary school in Pezinok he attended high school in Bratislava. Furthermore he decided to study in a collegial school for future priests in Šaštín. Here he was affected by the cruel Action “K” (Monasteries), which the communist regime commanded during the night of April 13 - 14, 1950. The goal of this action was to take over monasteries, later on also the convents. Consequently, the priests and friars in general along with Štefan, who was back then barely eighteen-year old boy, were moved to a concentration monastery in Podolínec. Since the regime didn’t manage to “re-educate” them, the younger prisoners were later on released. Štefan was able to continue his studies in Modra’s high school, although he was aware of the fact that in the back then Czechoslovakia, his greatest dream - to become a priest - would have never come true. Therefore in 1951 he made the first, but unsuccessful attempt to cross the borders with Austria. In October 1951 he made his second attempt to flee to freedom. A group of fifteen men headed from Šaštín towards the borders, so that they could later at night sail on inflatable dinghies across the river Morava to Austria. As he wanted to get to Italy, yet he had to overcome hundreds of kilometres through the Soviet, American, British, and French occupation zone of Austria. However, in spite of these dramatic events, before Christmas 1951 he was sitting by the desk at the University of Turin, where he began his philosophy studies. After the graduation his superiors sent him to a mandatory two-year didactic-pedagogical practice to France, where he worked in a little Ukrainian seminary in Loiret. Later he also taught French language in Italy and during his four-year theology studies, every summer holidays he accomplished this pedagogical practice in Germany. He was ordained a priest on July 1, 1959. In 1960s he achieved a Certificate of Proficient in English in Oxford, which he later completed by a conferment for English teaching in Rome. He extended his university education in Turin and in Rome, where he gained a degree of Philosophy Doctor. In 1968 he returned to Slovakia, however, his stay was interrupted by the joint forces of the Warsaw Pact which invaded Czechoslovakia. In Šafárik Square in Bratislava he convinced an Italian bus driver to take him along and this way he left his homeland again. Abroad he continued in his publishing and translating activities and for twenty-five years he worked as a priest and a professor in Italy. In the second half of 1980s he began to pursue only the insistent pastoral work and accompany Slovak pilgrims and visitors in Rome. He finally came back to Slovakia in September 1992. Besides the priest’s work he engages in publishing articles on various topics, as well as in translation and interpreting from English, French, Italian, and German. For seven years he also worked as a professional assistant in a detached workplace of Comenius University, in St. Thomas Aquinas Institute in Žilina, where he lectured philosophical disciplines.