Playing in the band was a “civic duty”

Download image

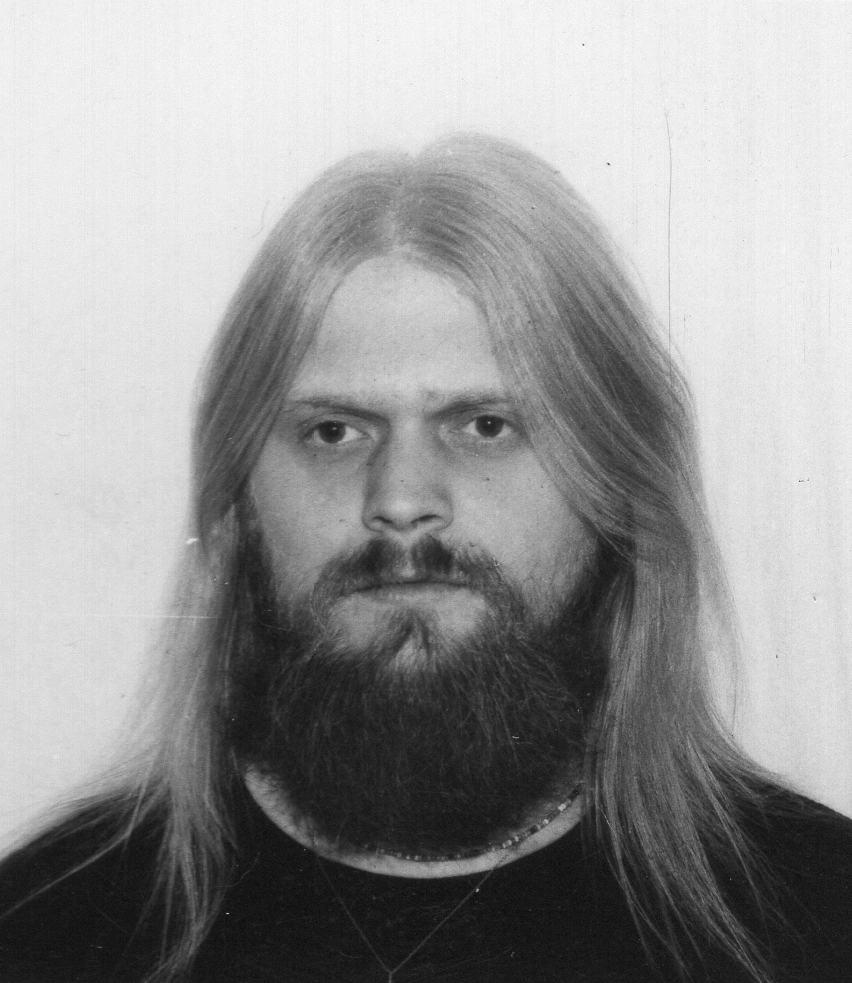

Vítězslav Škorpil was born on 9 December 1960 in Karlovy Vary. His parents worked in office professions. His mother, Jana, maiden name Kopecká, came from Humpolec, and her cousin was the later prominent representative of the underground Ivan Martin Jirous, who had a great influence on Vítězslav Škorpil. He also gravitated towards underground culture from his teenage years. He first learned about the underground from the television documentary Assassination of Culture (1977), which denigrated the bands Plastic People and DG 307. After finishing primary school, he graduated from the secondary school of economics in Karlovy Vary and took his first job in the office of the Karlovy Vary Earthworks. At that time, he had already founded his first band, Pepeško, which performed two concerts. In Karlovy Vary, he organized two private concerts by singer-songwriter Pepa Nos. After basic military service in Jirny near Prague, he returned to Karlovy Vary, where he worked as a gravedigger and later as an accountant for the State Farm. He performed in the bands Slunéčko netečné [Oblivious Ladybird - transl.] and Monotons and participated in several underground events. He became friends with local underground personalities, such as the poet Quido Machulka. He participated in the rewriting and distribution of samizdat and was interrogated by State Security about ten times. After 1989, in addition to his civic profession, he worked as a dramaturge for the Paderewski Cultural Club, which has been operating in the Husovka Theatre since 2009. He ran for the Karlovy Vary City Council on behalf of the Karlovy Vary Civic Alternative.