There is an opportunity hidden in every situation

Download image

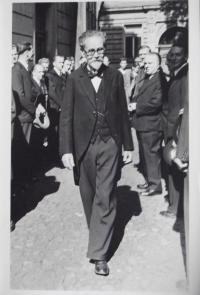

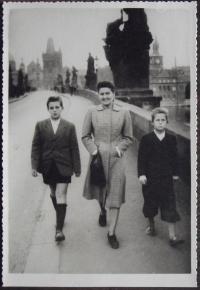

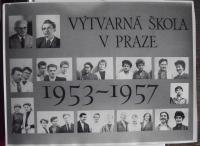

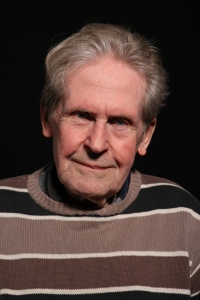

Václav Sokol is an artist, graphic designer and typographer. He was born in Prague on 19 September 1938 into the family of the well-known architect Jan Sokol, who acted as headmaster of the School of Industrial Art during the war. The witness completed a secondary art school (1953-1958), but his “bourgeois and Catholic origin” barred him from studying at university. In the years 1959-1967 he worked in the National Literature Memorial, and in the years 1971-1990 he was employed first as head of promotion, then as a graphic designer, and finally as a gatekeeper in the national enterprise Road and Railway Constructions. Since the 1990s he has mostly been working as a graphic designer, illustrator and free artist. In the years 1993-1999 he was active in the bi-weekly magazine Architekt (Architect). He helps prepare the typography of books (Triáda publishing house, Divadelní ústav - Theatre Institute) and he writes articles on visual art for Katolický týdeník (Catholic Weekly), Perspektivy (Perspectives) and Revolver Revue.