We’d stopped believing that communism would fall. We just hoped in secret.

Download image

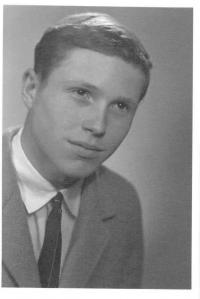

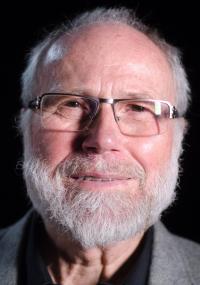

Ing. Mgr. František Srovnal was born in 1947 in Bludov. After completing studies at the Czech Technical University in Prague, he married Jitka Franková. Through Christian fellowships in Prague, they got in touch with people in the dissent. Srovnal also graduated from the Theological Faculty of Palacký University in Olomouc. After returning to Zábřeh na Moravě, they continued their quiet resistance to the regime. They distributed religious literature and samizdat [self-published] texts from Prague. They were among the organisers of home seminars in Zábřeh na Moravě, which were also often attended by prof. ThDr. Josef Zvěřina. In November 1989 the couple were in Rome for the canonisation of Agnes of Bohemia. There they heard of the demonstration on the National Avenue in Prague. In the early Nineties, František Srovnal was mayor of the city of Zábřeh na Moravě, where he lives with his wife to this day.