Přežil jsem, protože jsme byli málopočetná rodina, ti, kterých bylo víc, šli do Polska

Download image

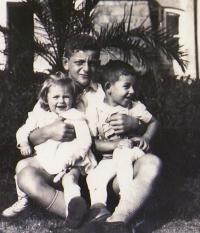

Igor Eli Stahl se narodil v roce 1934 na Slovensku v Bánovcích nad Bebravou. Jeho otec měl dopravní firmu a patřil k velmi známé a vážené židovské rodině v Bánovcích. Za Slovenského státu, v roce 1942, byl s matkou umístěn do pracovního tábora v Novákách, kde byl až do počátku národního povstání na Slovensku. Jeho otec byl transportován do ghetta v Lublinu, kde zahynul. Poslední válečnou zimu se museli s matkou skrývat s partyzány v horách nedaleko Donoval. Po roce 1945 byl majetek zavražděných příbuzných přepsán na pamětníkovo jméno, a tak se stal až do února 1948 jedním z nejbohatších lidí v Bánovcích. V únoru 1949 odešel do Izraele a od padesátých let žije v kibucu Kfar Masaryk. V izraelsko-arabských válkách sloužil jako tankista-mechanik. Má dva syny, manželka se mu před třemi lety zabila při autonehodě.