“I´ve turned around at the flash to see Mr. Gottwald falling down.”

Download image

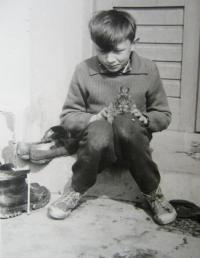

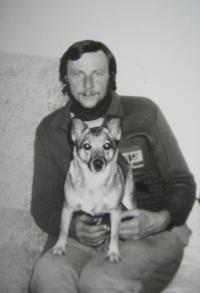

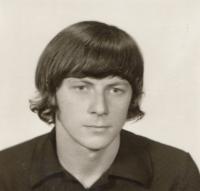

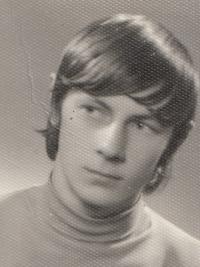

Mr. Ondrej Stavinoha was born on June 16th 1955 in Znojmo town. He comes from the working class family. Together with his mother, Mrs. Marie Stavinohova and his four years older sister he lived in Znojmo town for a short period of time. The family moved few times. At first to Velke Kralovice near Beskydy mountain region, then to a place called Svobodne Hermanice in Bruntal town region where they stayed for about five years and then they moved again, this time to Horni Benesov town. When Ondrej Stavinoha finished the grammar school here he entered the continuation farm school.Thrue his youth he was meeting frequently the negative attitudes regarding communists and the soviet soldiers. He heard similar opinions from his mother and the step father. After two years of the military training he started to work as a locksmith at the Pribram uranic mine. After one year he was accepted to work in the underground iron mine shaft. He liked to go out for a bottle of beer with his friends and just provoke the regime a little with the american flag on his jacket or by wearing the black clothes. Whit the upcoming 10th Anniversary of the occupation of Czechoslovakia Ondrej Stavinoha and his friend Frantisek Polak came to a conclusion that some major anti-regime event has to be arranged. Finally they have decided to fire away the bronze statue of Gottwald (the former president of Czechoslovakia) that was standing on the Pribram town square. They set off for the action at the night of August 22nd 1978. Ondrej Stavinoha placed about 1and a half of the explosive on the statue pedestal and detonated the statue. The statue flew into the sky in pieces after such blast. For the next seven days both of the participants went to their work as usual before the StB agents (communist state secret police) came to collect them after someone´s information. The curt trial took its place during January 22nd and 26th 1979 in Prague. Ondrej Stavinoha was sentenced to nine years in the correctional prison in Valdice town. Frantisek Polak was sentenced to seven years also in Valdice prison. Jaroslav Tysl, the explosive supplier, was sentenced to only one year. And since he spent already nine months in custody, he was free to leave the prison after just four months. The two main delicts of Ondrej Stavinoha were pronounced to be the sabotage and the illegal arming. After long nine years in prison Ondrej Stavinoha was free again. Thanks to his former chief he was admitted back to his previous job and started to work in the uranic underground mine again. After one year he married Milada Vejnarova. They were together for 16 years raising two children of hers. After they divorced, he began to live with his younger girlfriend who has two children two. He doesn´t have any kids of his own yet. Ondrej Stavinoha works in the military owned woods. He was given an appartment from his employer in Nepomuk village, where he recently resides with his girlfriend. He recalls the years spent in prison as wasted ears , time and everything but he tries to see it as a past left already behind.