I couldn’t smile for a long time

Download image

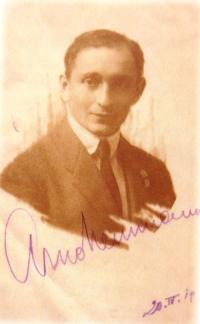

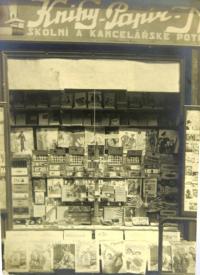

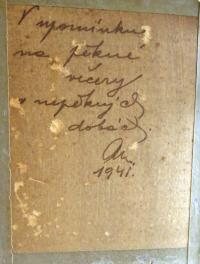

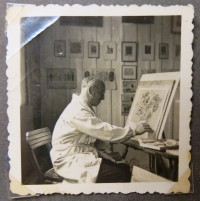

Hana Sternlicht, née Neumannová, was born on 10 February 1930 into an assimilated Jewish family in Prague. She grew up in Holice where her parents had a stationer’s shop. In 1940 Hana was expelled from school for being a Jew - she was home-schooled the following year. On 9 December 1942 she and her parents were deported to the ghetto in Terezín. She lived in the girls’ house L410. In September 1944 her father was transported to Auschwitz; Hana and her mother followed on 4 October 1944. After about ten days in Auschwitz, Hana was selected for work and sent to the Freiberg labour camp in Saxony where she worked in a factory producing aircraft components. In April 1945 the camp was evacuated and the female prisoners were taken to Mauthausen. Hana was liberated there by the American army on 5 May 1945. Both her parents and a large part of her wider family were murdered by the Nazis during the war. Hana returned to Holice but then moved to Prague a few months later; she and a friend were taken in by some family friends. She attended a business academy in Prague for two years. She was active in the Zionist movement Dror and decided to emigrate to Israel. She spent a year doing a preparatory Hachshara course in Liberec, in March 1949 she departed for Israel with her future husband, Hanuš Sternlicht. After her arrival she lived briefly in the kibbutz of Ha’Hotrim and the moshav of Arbel. In 1962 she moved to Kiryat Gat. She and her husband raised two children; Hana worked as a teacher at a school for disabled children.