“Bulgaria was the furthest country, where I could get under communism.”

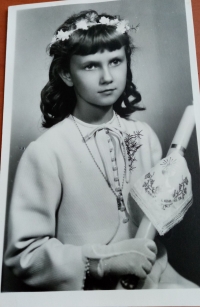

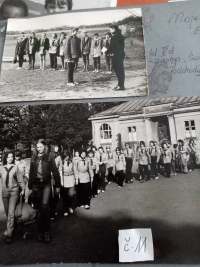

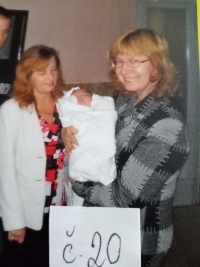

Renata Straková, as single Galkowska, was born on February 10, 1959 in Szamotuły. Her mother’s name was Daniela, as single Mlynska and father Kazimierz Lech Galkowski. On March 16, 1966, her brother Jacek was born. She went to primary school in the years 1966 - 1974. She studied at the grammar school in the biological-chemical class (1974 - 1978). She graduated from a university in the Bulgarian town Plovdiv, Department of Horticulture - Viticulture (1978 - 1982). In the third year, she married the Slovak man Peter, with whom she met on an mountaineering course. In 1982, a daughter Veronika was born, who was given czechoslovak citizenship. In April 1984, they both started working in state property in Nové mesto nad Váhom. They got a three-room apartment. Renata started as a hop- grower. In August 1986, a son Lukáš was born. In 1988 they moved to Trenčín and the husband started working as a steam boiler operator. Later, Renata completed additional university studies for teaching. She also received a certificate in German. She taught science subjects at primary school for six years. Together with a friend and a native from Katowice, Poland, they founded the Polish Club, Stredné Považie (2002). For the last nine years, she has worked at a social services center. She retired in 2021.