Simply no respect for authorities

Download image

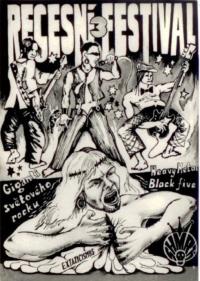

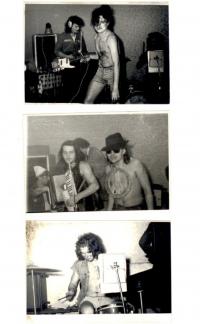

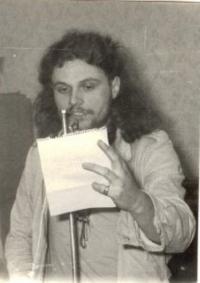

Libor Stržínek was born in 1958 in Prague. His father worked for the Czechoslovak army as a military counter-intelligence service officer. In 1968, he was transferred to Přerov, where the whole family settled. At the age of 11, Libor’s mother died in a tragic car accident. His father re-married but his two sons never really got to like his new wife. Therefore, Libor left his parent’s house at the age of 18. In the beginning, when he was on his compulsory military service, he was a member of the Union of the Socialist Youth but his world view would change radically soon. He was strongly influenced by the music band “The Sex Pistols” and by the so-called “rebellion music”. In 1984, Libor Stržínek, together with Ladislav Topič and Pavel Komínek founded the band “Loose association” that was later renamed to “Good old manual work”. He was the singer of the band and composed most of its songs. The texts of most of the songs were of an anti-Communist character. Therefore the band was prohibited from playing at public concerts and its members became the objects of interest of the secret state police. Libor Stržínek was interrogated several times and eventually he was allegedly convicted for denigrating the nation, race and conviction and was punished by a deduction from his salary for six months. After November 1989, he became a member of the Civic Forum and a trade union chief. He married in 1988 and lives with his wife and daughter in Troubky, where he witnessed the catastrophic flooding that took place in 1997. The whole street where he lived was flooded and all the buildings in the street - except for their house - collapsed. His wife and daughter had to be evacuated by a helicopter. He’s still the singer in his band Good old manual work.