The Seliger Community as an intellectual home

Download image

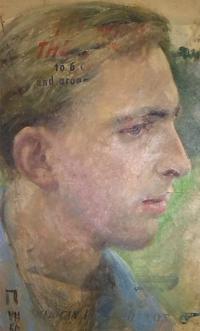

Johann Adam Stupp was born on May 15, 1927. The son of a successful businessman, he spent his school years at the Academic Gymnasium in Vienna. With the help of a friend, he was able to evade service in the Hitler Youth and when he was about to be drafted into the Wehrmacht in 1944, he managed to stay out of harm’s way by faking a heart disease. Having survived the first winter after the war in hunger-stricken Vienna and upon completing his secondary education, he went to study in Tübingen. Here he studied Protestant theology and also spent some time at the University of Lund in Sweden, where he met his future wife who was a Latvian. Finally he moved to Bonn, where he was a research assistant at the university and at the same time also had a job in the Archives of the upper house of the German parliament, the Bundesrat. In this position, Stupp got to know the leaders of the Sudeten-German Social Democrats, above all Roman Wirkner, his superior and at that time the chairman of the Seliger Community in North Rhine-Westphalia. In 1957, the family moved to Erlangen, where Stupp’s wife got a job as a doctor and Stupp himself, after some time, became the head of the Collegium Alexandrinum (Studium Generale). He held that position until 1993. In addition, Stupp got involved in various activities for the trade-union movement and published many essays about the Sudeten-German Social Democracy.