Ing. Václav Svoboda

* 1929 †︎ 2019

-

“It fell very close, because there was a frame-maker Hložek on the corner. He made picture frames. He had a beautiful daughter, a little older than me. I had a bike here. And when they pulled it off, we got almost - there was a bomb dropped, which shook our cover. Pieces of ceiling were falling down, we went to the wall, one girl clung to me there. The dust was inside… It took about a quarter or a half hour. Then it was over, they let us out. The square was covered with much dust and plaster. My bike survived; it laid on the ground upside down. I ran into it; the shop window was smashed at Hložek´s. I saw his daughter lying on the counter. Just a body torso. It must have fallen somewhere there. It undressed her. She had no legs, both hands… and was only in her panties. It was torn apart, just the rubber and the hill gone. Well, dead she was. I was only sixteen years old, and it was the first time I saw a young naked girl.”

-

Well, of course, [Dad] was crushed, disappointed, disappointed in people for they had become such hyenas. He said, “They must have known me so well that they knew that if they had come and said, 'Mr. manufacturer, we want to take it over here. We will give you a salary and we will employ you as an advisor.´ I do not dwell on property. I would voluntarily give it to them. That was the direction it was heading for. I would not be against it.” He was already sixty-four. And he knew he couldn't pass it on to the next generation. That was out of the question. He would have accepted it. Voluntarily and all. But if they could at least secured him a living. Because he dropped out of a factory without a single penny.

-

“There was much cheating. There were people chosen to be made into heroes. They created special working conditions on the shaft, they were preferentially supplied with material, machines, to achieve more (exceeding the norms). And then they honored them. When someone was working in the punching, he had no opportunity to achieve it, it was impossible. It was all ready, selectively. He did it for a while and then was made a hero, was assigned somewhere in the central committee.”

-

Když jsem skončil, kádrovej si mě zavolal a říká: “Podívej se, ty ses tu osvědčil a my tě tu potřebujeme. Nemáme dneska nějaký úřední [nástroj], že bychom tě tu přidrželi. Ale buď přesvědčen, že když odejdeš do Čech, napíšeme ti takový kádrový posudek, že od tebe pes kůrku nevezme. Půjdeš k lopatě. To je v naší [moci].”

-

Full recordings

-

v bytě pamětníka, 07.12.2015

(audio)

duration: 05:05:56

Full recordings are available only for logged users.

My father was not attached to the factory, he wanted to realize his ideas in it

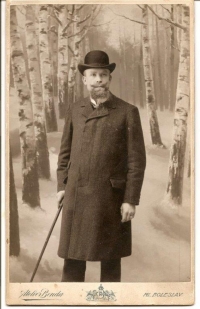

Václav Svoboda Jr. was born on May 25, 1929 in Mladá Boleslav in the family of Václav Svoboda, the founder of the Svoboda Motor Kosmonosy factory. His father was a well-known producer of small diesel-powered agricultural tractors in the 1920s and 1930s. Since childhood Wenceslas visited his dad’s factory, was interested in various crafts, and his father initiated him into his technological innovators. During the war, Wenceslas went to the middle class and later to a real grammar school. After the liberation, a factory council was set up in the father’s factory, which first dismissed all Svoboda’s relatives from employment in the summer of 1945 and then the owner himself in December 1945. The family remained without any income, for some time lived only from contributions of neighboring farmers. However, his father started to work again, this time as an employee of various companies. Václav had the opportunity to complete his studies and in 1948 he was admitted to the Czech Technical University in Prague. He finished school in 1953 and then he spent two years of service in the auxiliary technical troops /PTP/ in the Ostrava region. Here he applied his expertise as an electrical engineer and, after finishing his employment, offered him a job at the State Institute for Designing Coal Mines and Oil Industry Plants. He could not refuse such an offer, as any other employment prospects closer to home were immediately thwarted by the employer with a negative cadre assessment. Václav Svoboda therefore worked in Ostrava until the 1990s, when he retired.