My inner satisfaction with myself on fundamental issues is what somehow keeps me alive... I have paid a great deal of attention to it in every way

Download image

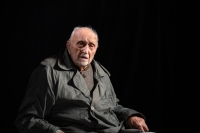

Ladislav Szalay was born on 23 May 1929 in Trnava. His mother’s family came from Moravia and moved to Trnava to work in a sugar factory shortly after the First World War. The family on his father’s side had Hungarian roots, but they were “slovakised” after 1849. His father worked at the District Court in Trnava until the 1950s, when he did not want to be involved in trials of people who had not handed their properties over to the state. Ladislav graduated from an eight-year Catholic grammar school and attended it during the Second World War. Ironically, at the school, he encountered the teachers’ rejection of the Slovak state’s clerofascist policies, and he himself saved a Jewish classmate from deportation in 1944. After graduating from high school, he entered the College of Commercial Engineering, but after the socialist coup d’état, his studies changed greatly. Subsequently, he was employed at the Institute of Economics of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, where, after initial teaching work, he began researching the economy of Slovakia between 1918 and 1928. As the research did not turn out as the reviewers had hoped, he had to end his scientific activity. He was employed in the editorial office of the journal Roháč until 1973, when he was dismissed after refusing to sign the consent to the entry of Warsaw Pact troops and the Lessons from the Crisis Committee. After three months on unpaid leave, during which Bilak’s son-in-law made it impossible for him to return to the academy, he was allowed to return to the editorial office at the lowest salary, even though he had the highest education. Shortly after November 1989, he founded the Slovak Daily (Slovensky dennik) and was behind the idea of founding a Christian party - the KDH (Christian Democratic Movement). Ladislav was entrusted with drawing up the program, but despite his electoral success, he was expelled from the KDH. After two years, the newspaper also disappeared. In 2018, Ladislav published a book on the centenary of Czechoslovakia called The Triumph of Propaganda.