The Nazis also intimidated children. He was nine when he had to watch the execution

Download image

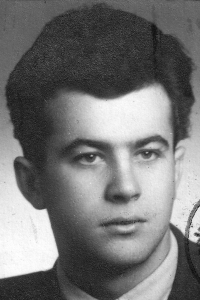

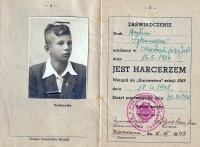

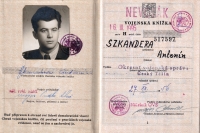

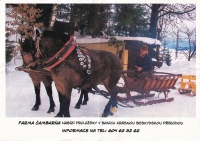

Antonín Szkandera was born on May 16, 1934 in Mosty u Jablunkova in the Silesian Beskydy. After the annexation of Těšín region to Nazi Germany, he had to go to a German school. His father was forced to work in the arms industry in Germany. The family claimed Polish nationality, but under pressure from the occupiers, the parents accepted a German document called a Deutsche Volksliste 3 (“Voluntarily Germanised”). The witness witnessed the execution of ten people in Mosty u Jablunkova. He and his friend found a corpse of a Soviet paratrooper. A witness to the liberation of the region in the spring of 1945. He trained to be a rolling mill operator in Třinec Iron and Steel Works. He worked in a rolling mill for heavy profiles. After completing industrial school, he worked as a shift foreman. He contributed to improving the working conditions of steel workers. In the 1990s, he started farming privately and engaged in agrotourism. In 2021, he lived in Mosty u Jablunkova.