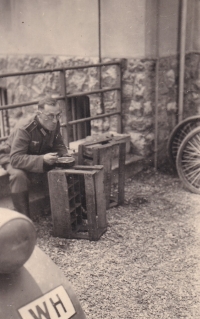

How beautifully we might have lived if the terrible war had not started

Download image

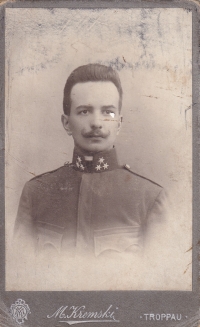

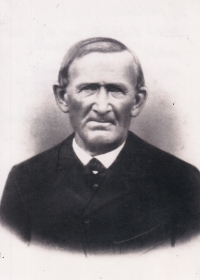

Kristina Tesková was born as Sonnková on 5 August 1939 in Hlučín, in the then German Reich. Her father was an artist. He studied at the Vienna Academy of Painting, but had to leave the school for the battlefields of the World War I. During the World War II, Germany drafted him into the Wehrmacht at the age of forty-eight. Kristina experienced the escape from the front to Moravia with her mother and brothers in April 1945. Meanwhile, their large house was occupied by the Red Army. They could never return there. After the Soviets left, the National Committee confiscated the house. Her father was captured in a camp set up for German prisoners of war in the former concentration camp at Auschwitz. Thanks to her brother’s illness, the family avoided deportation to Germany, to which they had already been assigned. When Kristina entered first grade after the war, she did not speak Czech. She worked as a clerk in several companies in Hlučín. She graduated from a two-year extra-mural school of economics. For the last ten years before her retirement, she worked as a housekeeper at the Hlučín grammar school. She married Vladimír Teska and had two children with him. She lived her whole life in Hlučín, where she was still living in 2022.