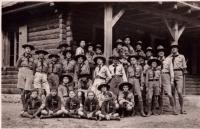

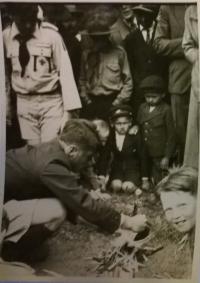

My whole life I have tried to live according to the Scout oath

Download image

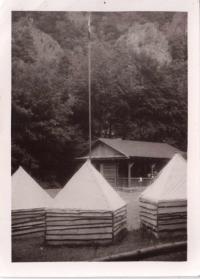

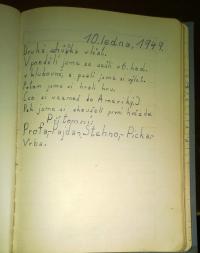

Jan Ivo Tomáš was born on 22 January 1922. Before the war he lived in Prague-Vinohrady. In the early 1930s his affiliation with the Rotary Club led him and his friend Felix Kolmer to join the Scouts Movement, and a few years later they co-led camps of the 18th Troop in Dejvice. During the war he worked as an electrician at Philips. On 8 May 1945 he was seriously wounded when the Germans hit the house he lived in when trying to bomb the Czechoslovak Radio. After spending three months recovering he decided to complete the university studies the Germans had barred him from undertaking; he managed get by with just a few weeks of compulsory military service. He also met with his friend Felix, who returned from Auschwitz in May. Together, they worked at the Department of Acoustics at the Research Institute in Prague until their retirement.