We thought the regime would fall soon, no one expected that it would last for forty years

Download image

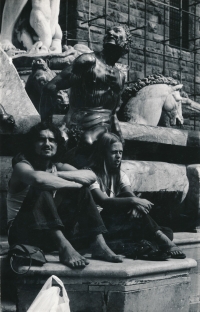

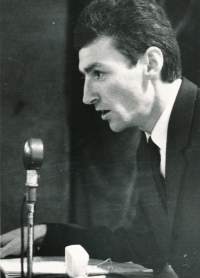

Miroslav Tyl was born in 1943 in Prague (Praha). His father was a lawyer who had participated in the anti-Nazi resistance and had been imprisoned in Theresienstadt (Terezín). Miroslav Tyl finished his studies in agriculture in Liblice near Pregue, becoming a cultivator and a breeder. He wasn’t allowed to study at university due to political reasons. He had to work as an agronomist at a farm in Radvanice for two years. After that, he had to do his compulsory military service; in the second year of his service, he had been listening to the foreign radio broadcast, he was charged with subverting the morals of the troops and given a mandatory sentence. He had been studying at the University of Life Sciences. He had also graduated in sociology from the Faculty of Arts in Prague. After he was elected a chairman of the Student council, he initiated an amendment to the Education Law, so attending multiple colleges at the same time was made possible. He was one of the leading figures of the Prague Spring of 1968 student movement and also one of the first to sign the Charter 77 petition. After the Warsaw Pact invasion, he had been working at a research department at some national enterprise. After 1989, he served as an advisor to two Prime Ministers and also as a member of parliament.