The Soviets were hard to come by. They always had to show that they had the upper hand

Download image

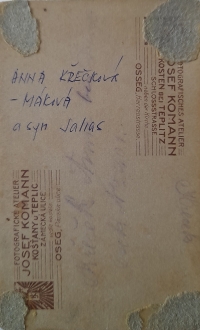

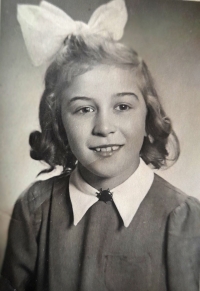

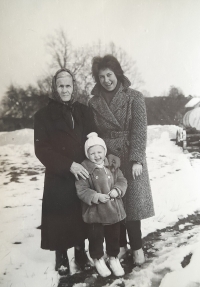

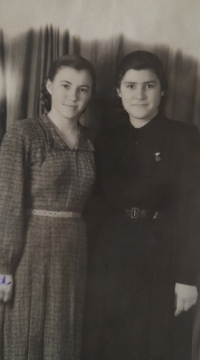

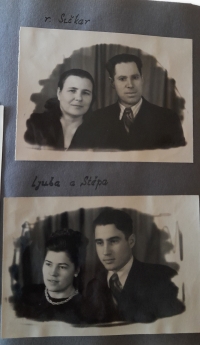

Marcela Ulrichová, née Máková, was born on 14 September 1939 in Prague into the family of Marie, née Horníková and Julius Mák. During the war, they lived in Všechromy in Central Bohemia with her mother’s parents. After the war, the family moved to Osek in North Bohemia, where the father, originally a stonemason and then a railway employee, came from. Marcela recalls the experience of war in Všechromy and also describes the atmosphere and life in post-war Osek, which Nazi Germany seized during the war. She went to school with children from mixed families. German families were evicted. Her parents divorced in the post-war years, and her mother remarried to a native of Osek, miner Rudolf Adelt. In 1948, Marcela’s brother was born from this marriage. Between 1954 and 1958, she graduated from the secondary school of economics in Teplice. She did not want to live in Osek and kept returning to her native region, where she married Jaroslav Ulrich in 1959. She followed him to Strančice, where they built a house. From 1960 to 1996, she worked as an accountant at Strojexport, located on Wenceslas Square in Prague. There, she took part in anti-occupation demonstrations between 1968 and 1969, for which she was expelled from the party in 1971, as was her husband. Their expulsion from the party made it impossible for them to travel abroad, and their daughter’s further education was at risk. From 1998 to 2010, Marcela’s husband, Jaroslav Ulrich, served as mayor of Strančice.