I appreciate people who were able to publicly stand up against that horrible totalitarianism

Download image

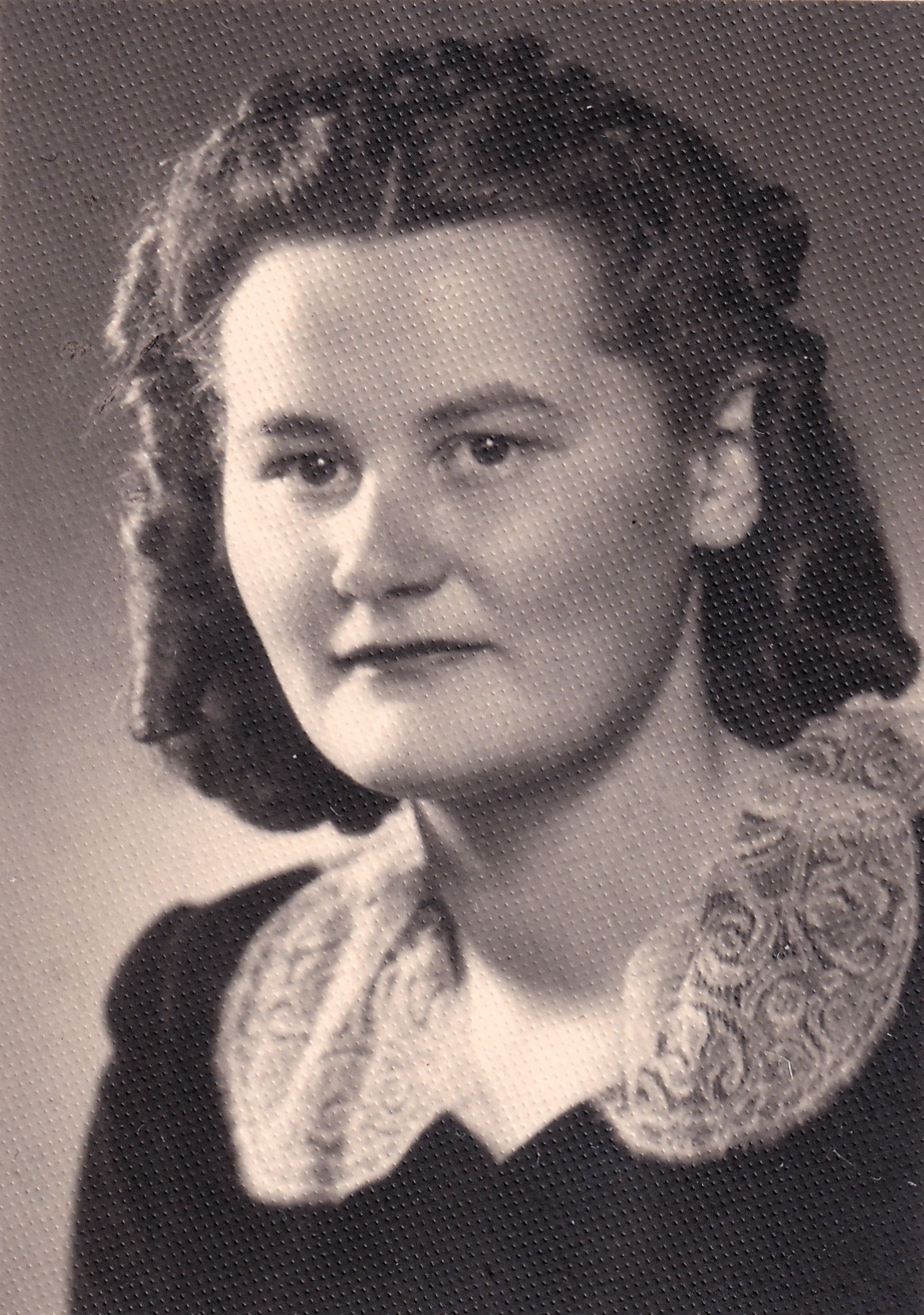

Věra Vacková was born on 28 February 1931 in Nové Město na Moravě. She spent her childhood in Žďár na Sázavou, where her parents taught at the local town hall and built a house in which the family lived through the war years. After the liberation, she became a member of a scout troop and a trainee of the local Sokol, with which she participated in the XIth All-Sokol Meeting in Prague. In 1948, her father, Karel Ronovský, a National Socialist functionary, was deprived of his right to vote and transferred to the distant town of Jevíčko. As a recent graduate of the grammar school in Nové město, the witness completed a four-week teacher training course in Hradec Králové and was placed in schools in the East Bohemian border region. After graduating from the Faculty of Education and entering into marriage in 1956, she moved to Prague. In 1989 she participated in the Velvet Revolution demonstrations. She worked as a teacher in Prague primary schools until 1993.