Oksana had to leave because she didn’t want to work for the Russian occupiers

Download image

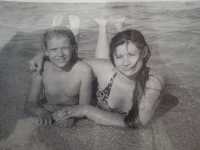

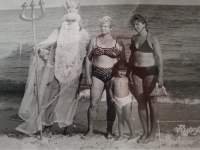

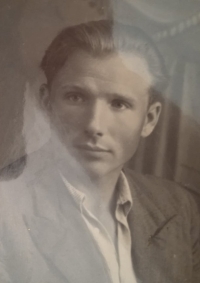

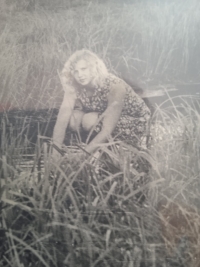

Oksana Valenková was born on 30 June 1980 in Melitopol. Her mother and father worked in a factory producing car parts, and Oksana and her sister lived with their grandparents. Oksana graduated from the Institute of Economics, has a daughter Maria from her first marriage, and now has two sons with her second husband. They lived in the village of Novoye near Melitopol, Oksana worked as an accountant and at the same time earned some extra money by growing flowers and vegetables. Her husband Denys worked in construction. They took in their elderly “uncle” Sasha, who had been deprived of his housing by speculators, and he lived with them and helped with various jobs. Already during the annexation of Crimea in February 2014, Oksana Valenková was afraid that the Russians would not stop. Although this did not come true then, Oksana remained cautious, for example, teaching her sons how to behave during shelling or an air raid. The Russian army occupied their village on the very first day of the war, 24 February 2022. On the third day, the Russians allowed the evacuation, and the family left for the border with Crimea in Novoalekseyevka. Local people helped the refugees by providing food and accommodation. Two weeks later, when the situation had calmed down a bit, they came back. Life was returning to the occupied territories and at the same time the new pro-Russian authorities began to function. Oksana refused an offer to work as an accountant at the university, considering it collaboration. However, they had to deal with the question of how to make their living, as her husband did not have a job either. They sold flowers and homemade sausages while watching the Russians establish their own order in the occupied territories. They set up a repressive regime, with the help of the army, preparing a referendum for annexation to the Russian Federation and also preparing the resumption of schooling according to their own curriculum prescribed by Moscow. Oksana finally convinced her husband that they had to leave. But before that, they carefully prepared for the so-called “filtration” process that anyone leaving the occupied territories must undergo. This meant, for example, deleting all potentially suspicious discussions or contacts, as well as “incorrect words” criticising the Russian army or regime. They successfully passed through a filtration point at the Crimean border and crossed Russia by bus to Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and finally the Czech Republic. In 2022, they lived in Chrudim and counted on it being a long stay.