Comrades turned their hatred to Máničky (young people with long hair) against each other

Download image

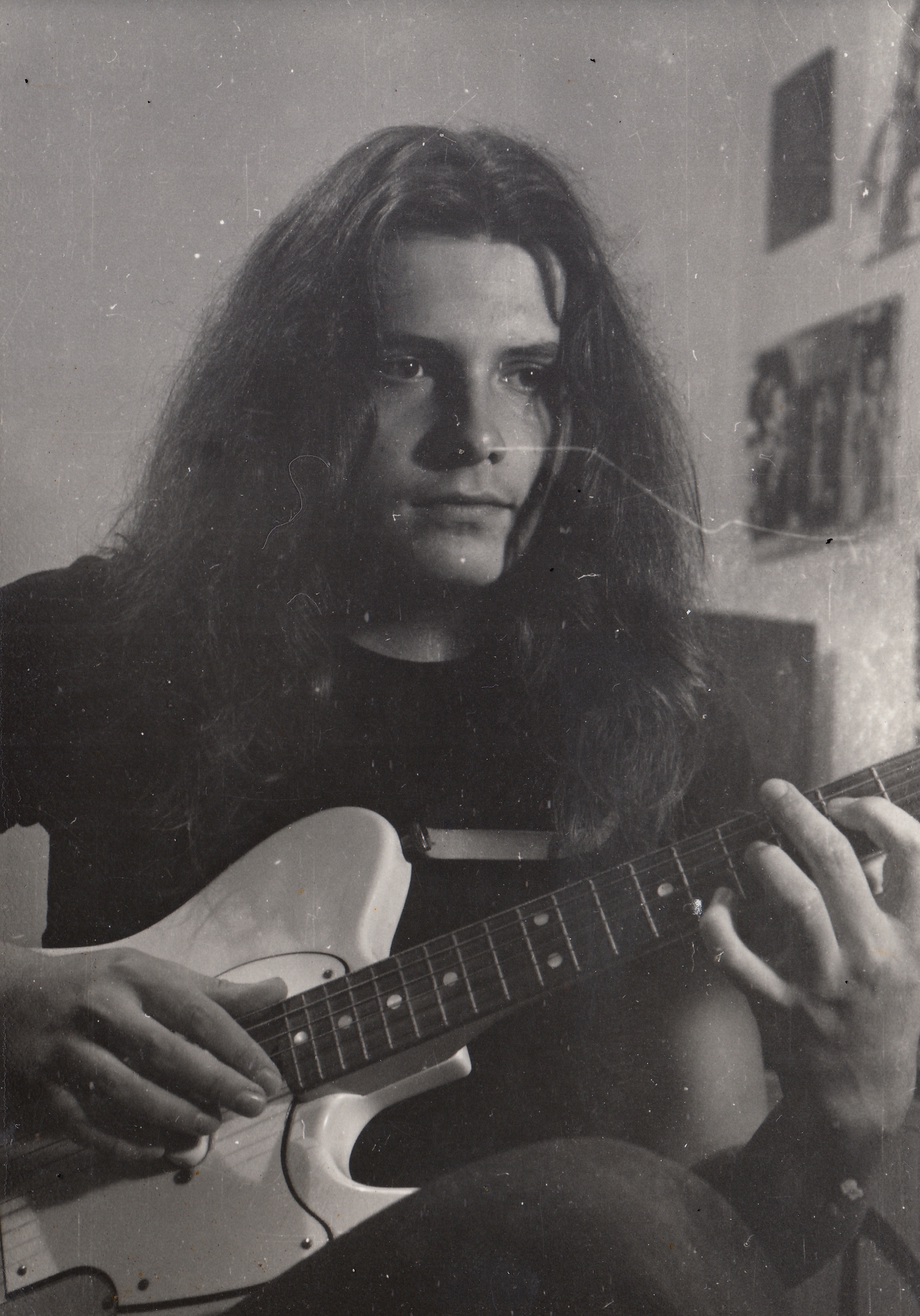

Robert Valík was born on 17 October 1957 in Gottwaldov. His grandfather was a Hussite priest and anti-Nazi resistance fighter Ferdinand Valík. Robert grew up in a family that made no secret of its negative attitude towards the communist regime. At the age of thirteen he fell in love with Western music, the desire for freedom, jeans and long hair. Already in high school, he had problems because of his appearance and he also struggled with the fact that the construction industry, which he entered in Gottwaldov in 1973, was then notorious for its harsh attitude towards “glitch youth”. Therefore, he left his studies at the age of seventeen and started working. Two years later he had to join the military service, but due to health problems with blood pressure he got out after only half a year, and a few years after that he was officially discharged from the army. During the 1980s, Robert Valík began to produce and distribute samizdat in cooperation with other Gottwald dissidents. In 1986 he signed Charter 77 and a few years later he was one of the founding members of the Gottwald faction of the Society of Friends of the USA.