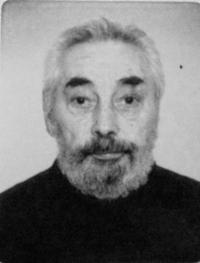

A class enemy

Download image

Petr Vaníček was born on March 15, 1932, in Prague. His father was a former legionnaire and the co-owner of a paint factory „Vaníček a Malec” located in Satalice in Prague. The war and particularly the Nazi policies aimed at the extermination of the Jews in Europe affected the life of the family in a cruel way. The Jewish members of the Vaníček family that didn’t manage to emigrate abroad in time found themselves in Nazi concentration camps. Petr’s grandmother died in the Theresienstadt ghetto. The family factory in Satalice was destroyed by the allies during an air raid that took place in the last weeks before the end of the war. It took nearly three years to rebuild the factory - the last worker left on February 21, 1948. A few days later, the Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia changed the life of the family for good. The factory was nationalized and Petr Vaníček - the son of an entrepreneur - was labeled a class enemy. He had trouble at school, was expelled, and had to take up studies at a different grammar school. Eventually, he wasn’t even allowed to graduate. In 1952, he was assigned to the auxiliary technical battalions (so-called PTP) where “politically unreliable” individuals were assembled for cheap labor in mines or construction. In the second half of the fifties, Peter engaged in distance learning at the University of Chemistry and Technology (VŠCHT). However, in 1958, he was expelled from the school after screenings had been conducted at the school. He was only able to finish his studies at the Faculty of Natural Sciences of the Charles University in the sixties. Although he always turned out to be an able and laborious expert, he was persecuted for his family background and the political views he held. Therefore he had to change his job frequently. He finally went to Slovakia where he could work in peace till the nineties. He currently lives in Prague.