Even the horses were going to war

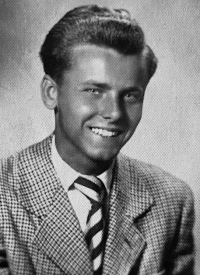

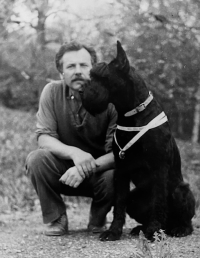

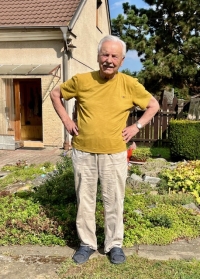

Download image

Karel Vlček was born on 30 April 1933 in Kutná Hora into a poor family. His father Karel Vlček worked most of his life as a worker in a chocolate factory, his mother Marie Vlčková, née Novotná, was a cleaner. He lived through the war in Kutná Hora as a primary school pupil. He witnessed the deportation of Jews, the bombing of Pardubice and Kolín in 1944, the escape of Wehrmacht soldiers to American captivity, the arrival of the Red Army and the subsequent executions of collaborators. In the 1950s, he knew some of the victims of the staged trial of Jaroslav Němeček. From 1945 to 1949 he was a member of the Scouts. In the 1950s he was not a member of the Czechoslovak Socialist Youth and admired American culture, so he only got into the Higher Forestry School in Písek on his third attempt. He completed his military service with the technical battalion at the Pardubice airport in 1957. Until his retirement in 1993, he worked as a construction manager at water construction sites, later as a construction supervisor and a forensic expert. He was a member of the Svazarm canine club and performed as a singer with dance orchestras for many years. After the revolution he became self-employed, designed sewage treatment plants and still makes well project, of which he has completed six and a half thousand. In 2024, he was living in Kutná Hora.