I wanted to do my profession and I was no hero

Download image

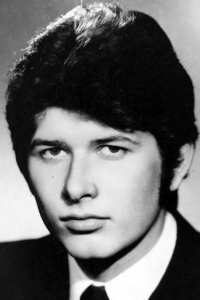

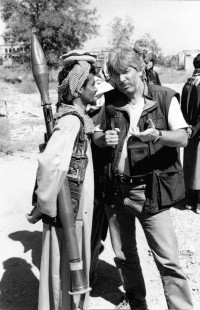

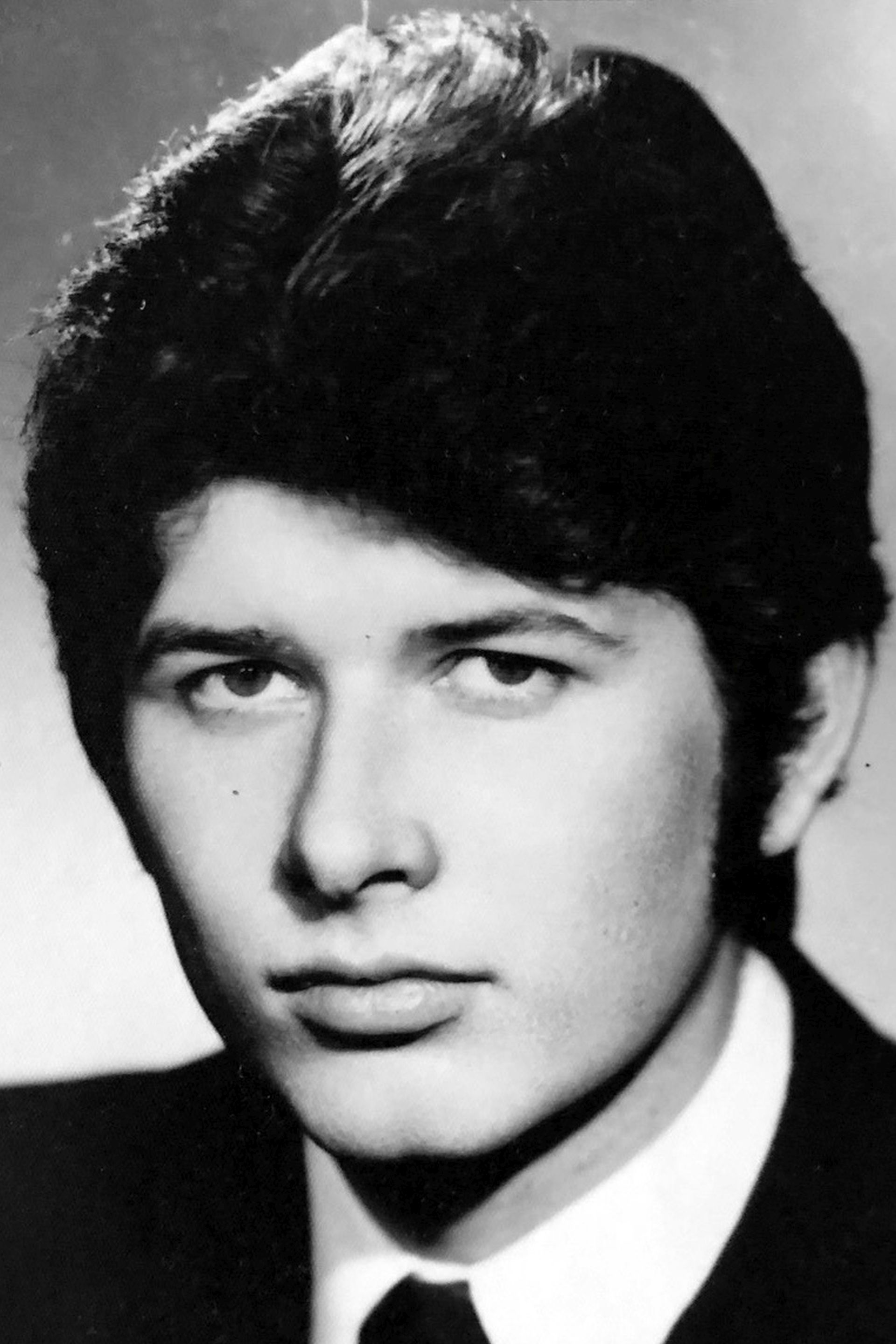

Petr Voldán was born on 20 December 1953 in Pardubice. His father was a soldier by profession. He spent his school years in Josefov and Tábor. He attended grammar school in Soběslav. He graduated from the Faculty of Journalism at Charles University in Prague. After his studies he worked as a reporter in the then Czechoslovak Radio. He joined the Communist Party. From 1987 to 1990 he worked as a radio correspondent in Moscow. He reported on the easing of conditions in the Soviet Union during the so-called perestroika. In the free world, he worked as the head of the foreign department of Czech Radio. From 1997 to 2000 he was a reporter from London. He spent the first four years of the 21st century again as a reporter in Moscow. In 2023 he lived alternately in Prague and in Zlič, in eastern Bohemia. As a pensioner, he worked with Czech Radio and Czech Television. Since the late 1990s, he has made more than ten series of travelogues for Czech Television.