Political commissars had a great influence in the army

Download image

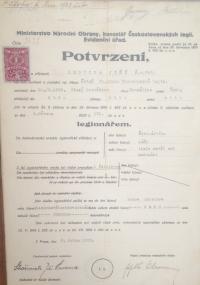

Václav Volfík was born in Postřekov on the 19th of September 1930. His father was a bricklayer’s labourer. Václav learned German in school during the war since his home village became a part of the Reich. After finishing school he became a coachbuilder’s apprentice in a nearby village in Bavaria. He witnessed the death marches in Postřekov in April 1945 and participated in the liberation manoeuvers with the American army. Between the years 1949 and 1952 he studied at military schools in Mladá Boleslav and Hranice na Moravě. He became a professional soldier and led an artillery regiment in Klatovy. After his promotion to a Major Václav left for a study stay in Leningrad for a year. He became an expert in missile technology and with his soldiers he helped built the first missile base in Slovakia. Between the years 1962 and 1972 he led a missile unit in Holýšov, after which he was transferred to Lysá nad Labem and became the leading officer of the local missile base. From 1982 he worked at the Ministry of Defence in Prague, retired in 1989 and returned to Postřekov, where he founded the so called Hall of Tradition.