When Dad was in prison we even had to take the thatched roof down to give the cattle something to chew on

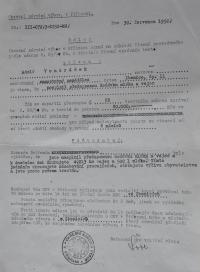

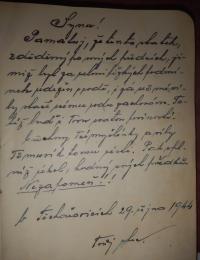

Adolf Vondrášek was born on 14 April 1937 in Těchařovice into the family of a large farm owner - their family farm had been established in 1540. After February 1948 his father was arrested, marked as a kulak, and imprisoned three times for allegedly failing to deliver his quota. With the threat of a fourth arrest looming, he committed suicide. After the father’s death, the family was evicted and forced to split up. The witness trained as a miner, but he felt a growing affinity for electricity, he understood broadcasting technology and could play on several musical instruments. All these skills became useful later on. During military service he was chosen to play in the army band and was also put in charge of the army radio service. After he was discharged, he took up employment as a miner, but his knowledge enabled him to participate in a seismological survey by the Academy of Sciences. He and his wife and three children were also part of the underground Catholic community grouped around Miloslav Vlk. After the revolution, Adolf Vondrášek became mayor of Mirovice; one of his accomplishments was to promote the construction of a memorial to the Romani victims of the Nazi regime in Lety Camp.