They came back from holiday, Dad was nowhere to be found and the doorsteps were ripped out

Download image

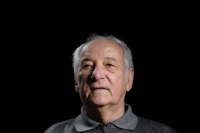

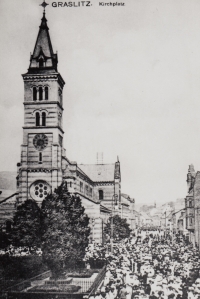

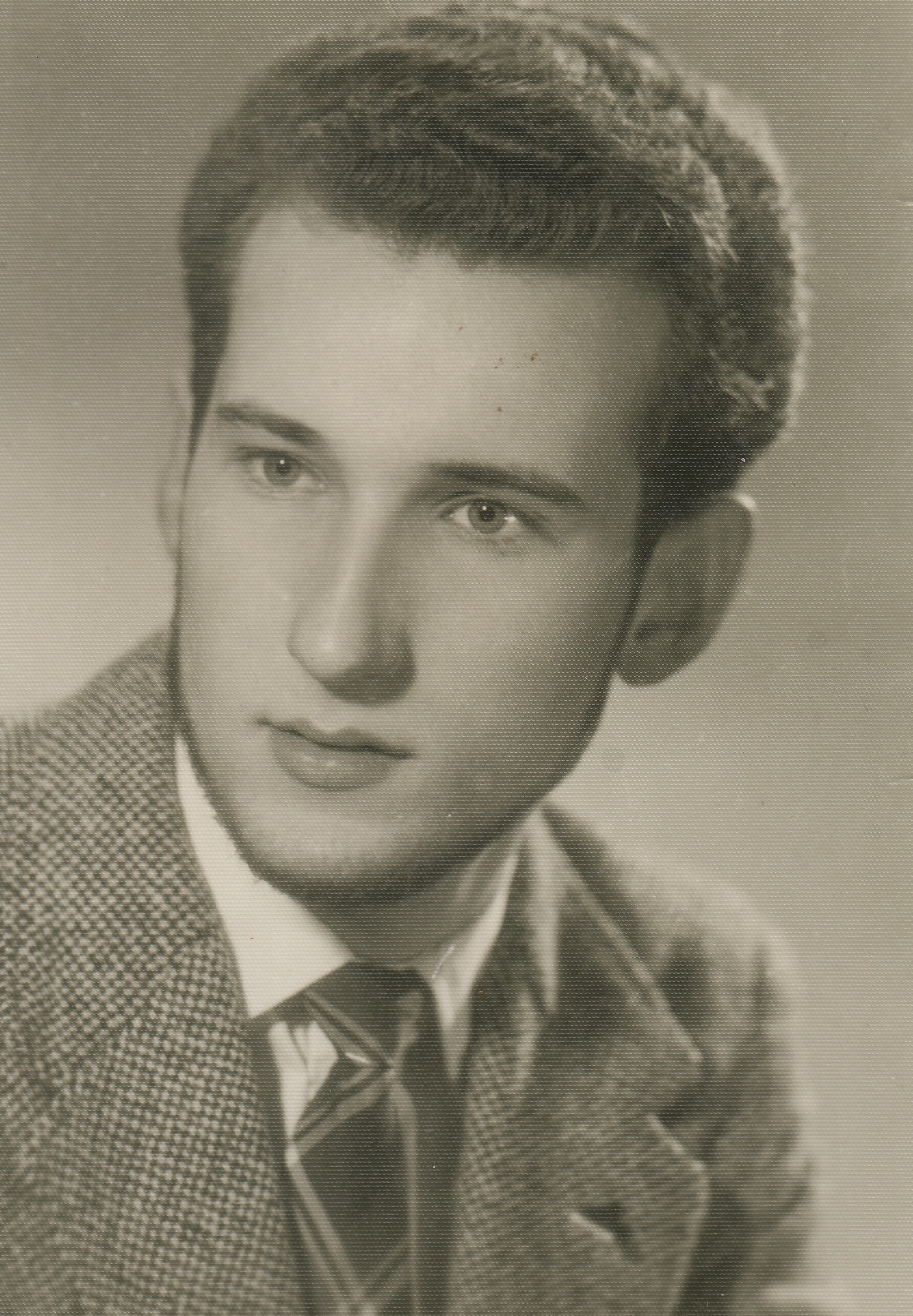

Jan Vosáhlo was born on 15 October 1942 in Rakovník, he had three siblings. He remembers Rakovník as a rich and cultural city. His parents moved there from Chlumec nad Cidlinou, his father Alois had a jewellery and watch shop in Rakovník, his mother was a housewife. In 1951, his father was arrested by the communist police and was sentenced to 18 months in prison. According to Jan Vosahlo, members of the National Security Service (SNB) searched his business and apartment for secret gold reserves. Jan Vosáhlo did not know whether they had actually found it. At the time of his father’s arrest and the search, he was spending his holidays at his grandmother’s house in Chlumec nad Cidlinou. His father was serving a sentence in Horní Bříza, West Bohemia, where he worked in a ceramics factory during his imprisonment. Mother and children could visit him only in pairs. The father was released in January 1953, a few months before the expiry of his sentence. In 1957, Jan Vosáhlo entered a vocational school in Kraslice, where he learned saxophone making. He graduated from the apprenticeship in 1960 and worked at the Amati company for the next 42 years. At the factory he met many Germans who worked there before the Second World War, when only a small Czech minority lived in Kraslice. In 1965 he married his wife Miroslava, in 1970 they had a son and in 1972 a daughter. Miroslava Vosáhlová and her parents came to Kraslice immediately after the Second World War from the Czech interior, her father was a maker of cases for musical instruments. In 1968, he and his wife were in France for a stay focused on Esperanto. In 1968, Jan Vosáhlo witnessed the Soviet occupation troops from neighbouring East Germany pour into the Czech interior through Kraslice on 21 August. He spent the next 21 years, described by historians as political and social normalisation, mainly working, caring for his family and playing sports. In 1984, he graduated from the Secondary School of Musical Instruments in Hradec Králové. He was chosen as a master in Amati, but had to become a candidate of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ). He did not join the party, however, as his candidacy was terminated by the Velvet Revolution in November 1989. In addition, he was in a dispute with the factory director and production manager before that and was dismissed as foreman. After 1989, after the opening of the border with reunified Germany, he witnessed Germans heading from Klingenthal to Kraslice for cheap shopping and restaurants. He remained at Amati after privatisation and left the company in 2002. In 2024 he was still living in Kraslice with his wife Miroslava.