After the end of the war, he hid from gunfire from liberators and escaped prisoners

Download image

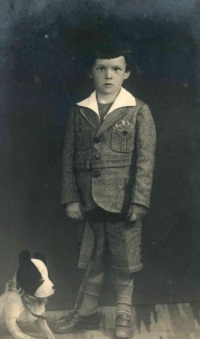

Bohuslav Vrána was born on 9 September 1930 in Harrachov, but the family soon moved to Lomnice nad Popelkou. During the economic crisis, his parents had to pay off their mortgage and were not in a good financial position. In 1943, the Gestapo arrested Josef Vrána’s father for listening to foreign radio, they interrogated him, but he did not give his acquaintances away. At the end of the war, on May 10, 1945, he experienced a shootout and a massacre of German civilians in Lomnica nad Popelkou. On the same day, the house of the Vránas was attacked by fleeing German soldiers. After the war, Bohuslav Vrána became an apprentice and later graduated from an industrial school in Mladá Boleslav. In 1952 he got married. His father-in-law Jaroslav Dědeček was forced to become the chairman of a unified agricultural cooperative (JZD) and had to evict his closest friends from the village, which he refused. Events related to collectivisation drove him to suicide. During the second wave of collectivisation in 1957, his brother-in-law at first refused to join the cooperative, but after pressure from the Communists he finally did. After 1989, the family acquired the property they had collected, and the deceased and his brother-in-law turned to farming. In 2022, Bohuslav Vrána was living in Žďár.