Charter 77 was a utopia made real

Download image

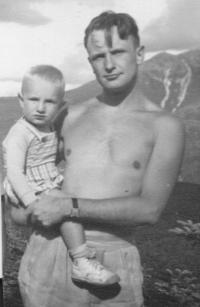

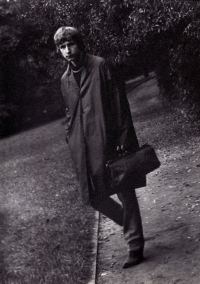

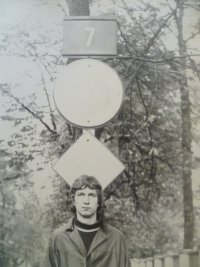

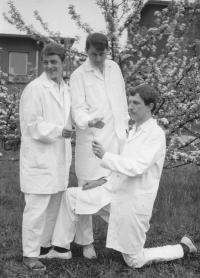

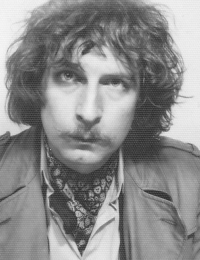

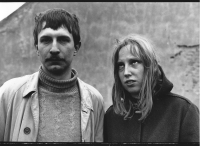

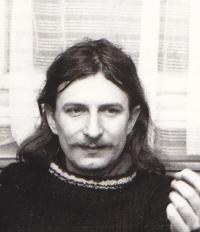

Tomáš Vrba was born on 30 November 1947 in New York to the Czechoslovak cultural attaché and translator František Vrba and his wife Libuše. The family moved back to Prague in 1950. The witness attended the grammar school on Velvarská Street and graduated from philosophy and psychology at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University in Prague. During his studies he took an interest in culture, art, and literature while growing increasingly critical of the Communist regime. From the mid-1970s he helped distribute and publish samizdat, he attended flat seminars and banned cultural events. After signing Charter 77 in January 1977 he and several of his colleagues were dismissed from their jobs as social curators for Prague Romanis. Until the collapse of the regime he worked in manual and technical professions while continuing his organising and editing activities, among others, for samizdat series (Kvart, Expedice) or independent periodicals (Spektrum, Kritický sborník). In 1989 he took an active part in the forming of the Civic Forum and the restructuralisation of society - he served briefly as an adviser to the mayor of Prague and for a number of years in the Association of European Journalists and the Central European Seminar in San Sebastian. In the 1990s he worked as the chief editor of the culture magazines Lettre internationale and Přítomnost (The Present). Around the turn of the millennium he began lecturing at the New York University in Prague, he joined the board of directors of the Forum 2000 Foundation and chaired the board of directors of Archa Theatre. He continues in the last three of the aforesaid activities to this day, along with the occasional translation from English and his editorial and publishing work. As of 2017, the witness lives and works in Prague.