The cows and horses I had were really fine and exquisite. Later they became the basis for the kolkhoz that the communists established.

Download image

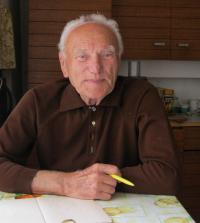

Květoslav Vrtěl was born in 1922 in Polkovice in the region of central Haná. During the war he was sent to do conscripted labour in the village of Mönchhof, Austria, where he was digging antitank trenches. In 1950 he married Věra Jedličková, and he took over a part of the family farm. When the Unified Agricultural Cooperative (JZD) was being formed in Polkovice, he and his father refused to join. The amount of prescribed delivery quotas and taxes were thus proportionally increased for them, their agricultural machinery was confiscated and their fields were exchanged for worse and more distant fields. In spite of all this, they did not join the JZD until 1958. They were eventually sentenced as a warning to others. Květoslav was given a one-year sentence, and his father was sentenced to six months. Their farm buildings and all cattle were confiscated. Květoslav Vrtěl spent several months in the Mírov prison and then he was interned in agricultural labour camps in Sýrovice and Oráčov. After his release he continued working in agriculture. Today he still lives on his native family farm.