Sometimes, there was a black banner flying in there

Download image

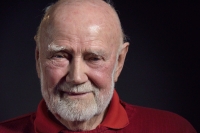

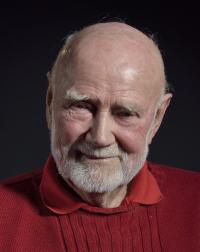

Jan Vůjtěch was born on 8 June 1950 in Prague. Following his father’s example, after WW II he went to study law at Prague’s Faculty of Law. However in the final year of his studies he was expelled for his political opinions and instead was drafted to do his military service. As a politically unreliable person, he was assigned to the so-called Auxiliary Technical Battalions and sent to work at a coal mine in Silesia named after President Gottwald. Here he worked as a miner at the shaft and later, being an “intellectual skilled in reading and writing”, as a manager ensuring the miners’ material well-being. Before the end of his service he sustained a leg injury. In 1954 he returned to civilian life, finished his law studies and worked in the state Enterprise for Foreign Trade. At the same time he also managed to graduate from philosophy and psychology. After the August 1968 invasion he worked first as a garbage collector and later as a scientific researcher. At the end of 1989 he became active in the Civic Forum and then worked as head of the advisors and a clerk in the Czech Parliament. In 2003 he went to retirement. Ever since he has been active as a lawyer in the Auxiliary Technical Battalions Association, helping its past members file successful compensation claims.