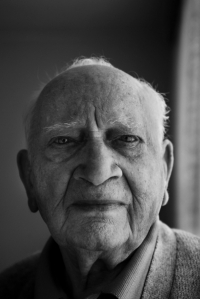

I never stopped hoping that they wouldn’t execute me

Download image

Ján Zeman was born December 20, 1923 in Myjava in West Slovakia. His childhood was affected early on by the loss of his mother and his father’s emigration to the USA. He grew up with his grandparents in Myjava. Following his father’s footsteps, who had inherited smithery from his ancestors, Ján decided to be apprenticed after completing primary school. After one year in the armory in Považská Bystrica he switched to a technical high school of machinery in Bratislava, which he successfully graduated from. However, instead of further studying he had to start working since his father, who had been living overseas with a new family, couldn’t support him during the World War II times and Ján’s grandparents needed financial support. He soon rose to the position of the head of construction in the Tauš factory in Myjava where fittings were made. In 1947 Ján, then just 24-years-old, even received a state award for his work immersion. He was also successful in his private life during the first postwar years. He married Olga Sandanusová who he had known since childhood, in 1947. In March 1949 he was contacted by Štěpán Gavenda, an agent-strider, who arranged messages from Czechoslovak informants to Western intelligence services under the leadership of František Bogataj. Based on Bogataj’s letter that Gavenda handed him, Ján decided to heed the call and join the anti-communist resistance. Using dead drops, he then transmitted information on the type and volumes of arms production or the numbers of employees and militia men of the factory. After transmitting five encrypted messages, he and his wife, who had worked with him, were arrested in August 1949. A trial took place early that fall after cruel interrogations. Ján was identified as the head of an anti-state group and was sentenced to death together with Viliam Šimek. His wife Olga was sentenced to fourteen years in prison. Ján spent nine months on death row in solitary confinement in Leopoldov. In 1951 his death sentence was changed to a life sentence thanks to Klement Gottwald’s presidential pardon and, above all, thanks to his father’s tireless efforts and the intervention of the U.S. embassy. He went through the Jáchymov and Příbram camps, returned to Leopoldov in the times of its tightened regime, spent many years in the Opava and Mírov prisons and then his last three months in Valdice. Olga spent eight years of imprisonment at various locations – Ilava, Pardubice, Želiezovce. She suffered infective hepatitis while in prison and developed severe diabetes shortly before Ján’s release. In February 1964, after fourteen and a half years, Ján and Olga finally met in freedom. They again settled in their home Myjava where Ján found a job in the newly established District Industrial Plant. In 1970 they even travelled to USA to see Ján’s father but came back even though they could have stayed there with such a good support environment. During the Velvet Revolution Ján became a founding member of the Myjava cell of the Public Against Violence and was elected to the city council after the first free election in 1990. In 2010 he was awarded the Václav Benda Award granted by the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes. In 2014 he received a state award from president Andrej Kiska and one year later an award from the National Memory Institute. He still lives in Myjava (as of 2020).