Ich schämte mich, dass das Haus früher den vertriebenen Deutschen gehörte. Das war ein ungutes Gefühl.

Download image

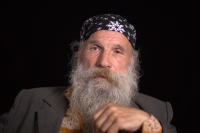

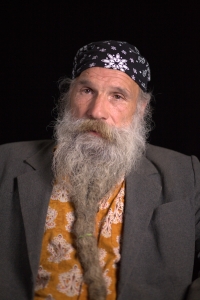

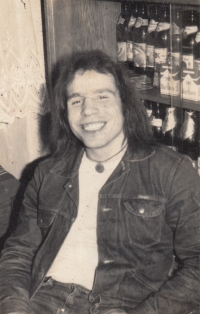

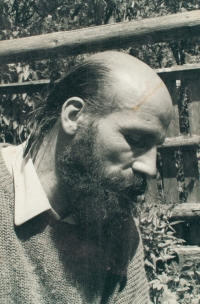

František Klišík gehört zusammen mit seinem Zwillingsbruder Ondřej zu den Nachkommen der rumänischen Slowaken, die nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg auf Einladung der tschechoslowakischen Behörden kamen, um die verlassenen Grenzgebiete zu besiedeln. Die Familie Klišík ließ sich in Stögrova Huť bei Volary nieder, einem Dorf, das nach dem Krieg nie wieder vollständig besiedelt werden konnte. Jahre später kam die ursprüngliche Besitzerin aus Deutschland, um ihr Haus zu sehen. „Ich schämte mich dafür, dass es einst ihnen gehörte“, beschreibt František Klišík seine damaligen Gefühle. Weder František noch sein Bruder fügten sich gut in die Schule ein, sie sprachen daheim nur Slowakisch und nachmittags gingen sie Kühe hüten, anstatt zu lernen. “In der ersten und zweiten Klasse waren wir komplett isoliert, niemand wollte mit uns reden. Kinder können grausam sein. Es kam vor, dass uns die ganze Klasse durch Volary jagte. Einmal, als es kalt war, ließ uns die Mutter den Schlafanzug an und wir zogen unsere Kleidung darüber. Als wir uns für den Sportunterricht umzogen, lachten uns unsere Mitschüler aus. Weil wir so angezogen waren und schmutzige Hände hatten, ohrfeigte die Lehrerin uns.” František schloss seine Schulausbildung in der siebten Klasse ab. Er sagt, das Gasthaus sei die Universität seines Lebens geworden. Er kam mit Menschen aus dem Umfeld des Underground und der Dissidentenbewegung zusammen. „Nach dem Wehrdienst bin ich da in Prag hineingerutscht und habe Leute kennengelernt, mit denen ich heute noch befreundet bin.“ Im Sommer 1989 sammelte er Unterschriften für die Petition ” Ein paar Sätze” und nach der Samtenen Revolution gründete er Bürgerforen in ganz Südböhmen. Text pochází z výstavy Paměť hranice (nejde o překlad životopisu). Der Text stammt aus der Ausstellung Das Gedächtnis der Grenze (es handelt sich nicht um Übersetzung der Biografie).