I advocate a thick line. I consider forgiveness to be a fundamental Christian idea and the most important message of Christ. The way of reconciliation is more rational than the way of revenge.

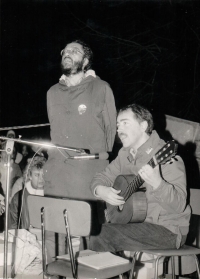

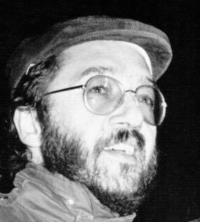

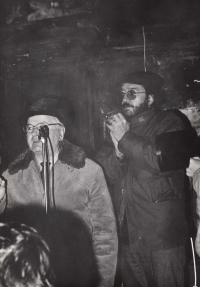

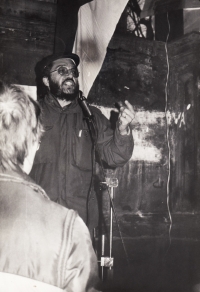

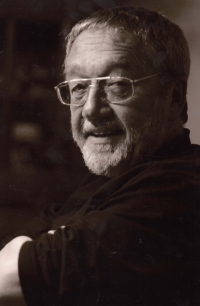

Zdeněk Bárta was born on 22 March 1949 in Prague’s Smichov. In his childhood, he was influenced by his grandfather - a patriot, a Protestant and a Masaryk-like Democrat. In the church of St. Martin in the Wall he met Svatopluk Karásek, who later inspired him to study at Comenius Evangelical Theological Faculty. He began as a pastor in 1974 in Chotineves in the Czech Central Mountains, where his parishioners were mainly Vollynian Czechs, resettled here after the war from Boratin in Ukraine. Barta organized seminars where he invited important figures of the dissent. Worship and meetings were also attended by people from the underground community in nearby Řepčice. After signing Charter 77 in 1979, he lost state approval to pursue spiritual activities. He stayed in Chotineves and devoted himself to religious life. At the same time, he worked for eight years as a meter reader before his consent was returned. In November 1989, he founded the Civic Forum in Litoměřice, worked in the Czech National Council for two years and in 2004 - 2010 he was a senator for KDU-ČSL. In 2014 he became a member of the Council of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes. He co-founded the Diakonie branch in Litoměřice, where he is now Deputy Director. He is a priest in Litoměřice. He is married and has four children.