Despite being threatened with being shot dead, her mother pulled her out of a house on fire

Download image

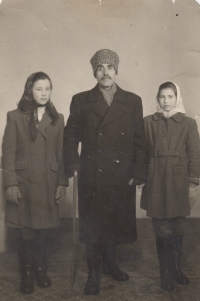

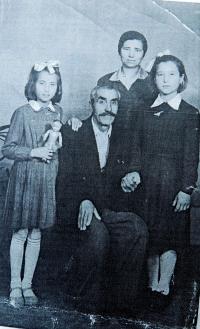

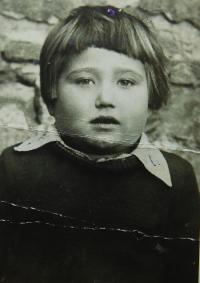

Irini Bulgurisová, née Tcapas, was born on the 10th of February 1943 in the town of Maniaki (Kolorica in Macedonian) located near the lake Kastoria in northern Greece. Her family was one of the Slavic Macedonian ethnic groups living in Greece who spoke various Macedonian dialects among themselves. During the civil war in Greece her father fought for the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE). In 1945 their family home was set on fire by men from an armed militant right-wing group. They were looking for Irini’s father who was hiding in the mountains at the time. The flames trapped the disabled grandmother and just two years old Irini. Despite threats of being shot to death, Irini’s heavily pregnant mother dragged them out of the house. Around the end of autumn 1948 the mother along with five year old Irini, her two year old daughter Vasiliki, and the grandfather escaped across the border to Albania. The family then separated. Five year old Irini spent several months in an orphanage in the Albanian town of Elbasan and then five years in an orphanage in Fehérvárcsurgó in Hungary. After spending several years away from her family, little Irini almost forgot her parents and the orphanage became her world. Only eight years after the war the whole family finally reunited in Vrbna pod Pradědem. Irini married before reaching the age of 18 to Fotis Bulguris who was from a town called Chiliodendro (Želin in Macedonian) and whose dramatic escape from Greece is also recorded in the Memory of Nations archive. The couple later lived together in the town of Javorník, located on the north-eastern side of Rychlebské mountains, and still lived there as of 2017.