I was fifteen when I persuaded my mother to emigrate with me.

Download image

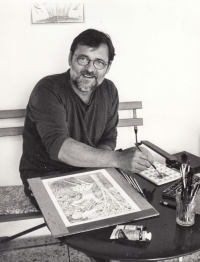

Internationally renowned illustrator and graphic designer Jindra Čapek (his own name is Jindřich) was born on 30 September 1953 in České Budějovice. His father, František Josef Čapek, was expelled from studying architecture at university because of his poor class background and, as the son of a tradesman, had to join the technical battalion. Grandfather Josef Čapek co-founded scouting in České Budějovice. Jindra Čapek painted very well since childhood. In 1969 he successfully passed the entrance examination to the Secondary Industrial School in Turnov. Instead of studying, he persuaded his mother Marta to stay in the West, where they went on holiday together. At the age of fifteen, he emigrated with her to Switzerland. He was granted asylum there and studied at the secondary school of arts and crafts in Zurich and the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe, Germany. After his studies, he began working with the exiled publishing house Bohem Press in Zurich, and later with other European publishers. To date, he has illustrated over 70 books, which have been translated into 30 languages. He has won numerous international and domestic awards for his illustrations. He has exhibited his work all over the world. In 2021 he lived and worked in Český Krumlov.