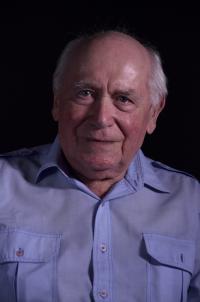

When you live, you should live in full

Download image

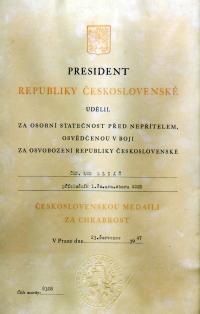

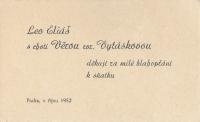

Leo Eliáš was born on 5 January 1921 in the town of Sečovce in eastern Slovakia. In 1942 he was drafted into compulsory military service in the labour corps, mainly as a digger. At the beginning of the Slovak National Uprising he participated in the celebrations in Banská Bystrica. He applied to join the 1st Czechoslovak Rebel Army and was armed and equipped in Zvolen. He was first posted as a guard for the waterworks in Banská Štiavnica. He was injured while defending the hill above the village of Sandrika. When the hospital in Banská Bystrica was evacuated, he was taken to Sliač, and from there to Lviv by a plane that had delivered military cargo for the uprising. After spending a month recovering in the Kiev hospital, he received a travel order to Krosno in Poland. There, he volunteered in the 1st Czechoslovak National Corps. He served as a guard at the military court, public prosecutor’s office, and other places. He escorted his superior, Doctor František Vohryzek, on his journeys to the army headquarters. The end of the war found him serving in Liptovský Svatý Mikuláš. His service in the military corps took him all the way to Prague, where he demobilized at the rank of sergeant after about seven months. He started work at the national enterprise Tatra, where he worked as a car repairman until his retirement.