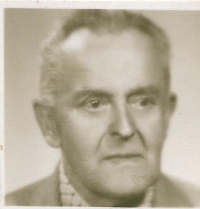

„In 1941, he had to enlist to the Wehrmacht. At the end of June, after the invasion to Russia, they were transferred to the Eastern front, the bit towards the north. He got as far as – in 1941 – to Rzhev, with his unit. When I was a boy, I asked him many times: ‘Daddy, how was it there in Russia when you were in the army?’ He had a plenty of photographs which I still have at home. But he never wanted to talk about it. All I know, I know it from my mum. He wrote letters to her, he told her stories, too, but they burned the letters after the war. Dad would always say: ‘You know what, my boy, the further to the east, the smaller the windows and the larger the bedbugs. What could I tell you about Russia.’ That was the end, he never told me any more. How they lived there, what was going on, that’s what I know from mom a bit, that story of his. He said that the fights were terrible.

That massacre of Russian soldiers… That’s actually true what they say, that they chased a wave after wave against the German positions. Before their positions, dead bodies piled up and others had to run over them. He would say: ‘My friends were falling dead aroundme but I survived.’ He was injured about three times. He showed me the scars. Once, he was shot through the stomach, he survived that, then he got hit in his leg and the third casualty, I’ll tell you later. He had some sort of guardian angel. Of those guys managing their cannon, six soldiers were needed to do that, three or four fell. I have photographs of dad standing by their graves. Then in 1943, they pulled them back from the Rzhevsk area to Belarus, somewhere around Vitebsk. Their unit was pretty decimated so they got reinforcements. Meantime, the front advanced and in summer 1943, it reached Belarus. They were there for quite long, until summer 1944. When there was that huge Bagration offensive, their division took part in this operation. Only seventy soldiers were left from their division after that attack. Out of nineteen thousand. It was totally shattered. He was one of those who survived. So they transferred them to reinforce some grenadier division. He ended up in Kaliningrad – Královec. The town which was founded by Přemysl Otakar II. [a Czech king], today, it’s a part of Russia. Královec was under siege, they remained there for long, until April 1945. My father was badly hit by shrapnel from Katyusha. He was lucky to get to one of the last hospital ships to the rear. They extracted most of the shrapnel. He was lucky even there. He got high fevers on that ship. At that time, a First Commander who was in charge of the of the lower decks, walked through. It was dad’s schoolmate from Liberec. He passed by, stopped and told him in German: ‘Ernst, was machst du hier?’ [Ernst, what are you doing here?] Dad was delirious. The officer called the medic immediately: ‘You transfer this bloke to my cabin, he’ll get medicines and everything he needs, he has to survive!’ He got to the rear, they got him out of it there. He was captured by the British and the Allies at the West released the badly wounded. They were not as cruel as Russians. He was in that field hospital all that time. The doctors cured him, in August 1945, he was healed and in September 1945, they released him. The doctor advised him: ‘Don’t even think of giving them your addres in Bohemia or else they’ll hand you to the Russians.’ So he gave them an address in Selb, where his in-laws lived. I still have his release papers, in English. So he got a train ticket and went to Selb. During the night, he crossed the border to Hazlov.“