I’m the child of a country of two peoples

Download image

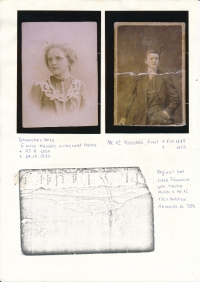

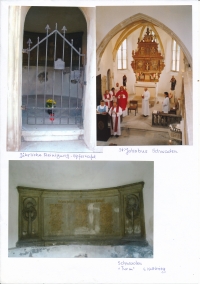

Brigitta Gottmann, née Kaschte, was born into a lower class family on 11 April 1939 in Svádov. During the war, their father reached the position of stationmaster in Velké Březno. They lived for several years in the service flat of the station building, after 1944 only the mother and her three daughters lived there. Brigitta associates her memories of the end of the Second World War with this railway station in particular. In April 1945, they had to leave the flat and Brigitta, along with her mother, aunt and two sisters, left for Sebuzín, where their grandmother on the father’s side lived. On arriving in Sebuzín, their mother wanted to commit suicide with her children in the river Labe. In the end they survived a few weeks, working in strawberry fields, and were deported through Cínovec to the refugee camp in Saxony. After primary school, Brigitta went to the surface mines as a locksmith / lathe operator. Then she wanted to study at the agricultural faculty, but missed her training deadline and ran away to her sister in the West, in Lüdenscheid. She soon married and had three children. Since the 50s, she has been a very active member of the Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft. Due to her childhood experiences, she has suffered from anxiety and at her therapist’s recommendation she often returns back to her place of birth. She collected money to help fund the reconstruction of the Svádov church and to build a hospice. Today she continues to initiate meetings of witnesses and works primarily with Czechs from among the clergy.