In the 1960s, the wounds of the wrongs of the 1950s were not yet healed

Download image

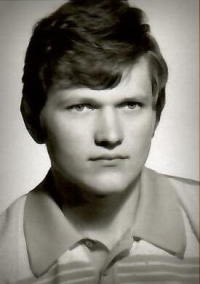

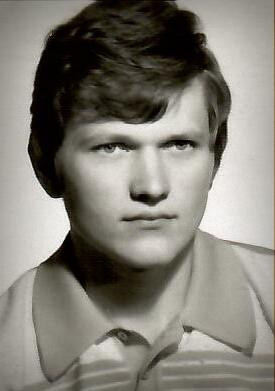

Vladimír Gut was born on 18th October 1956 in Vlašim, he grew up in the nearby village of Radošovice, in a family that had its own farm until 1957. After the communist takeover, the Guts’ house and the hospitality business it was part of were nationalized in 1957, along with all the fields. In Radošovice, a joint agricultural cooperative was established in 1951, following the example of the Soviet Union, and most of the Radošovice farmers joined it then. Vladimir Gut’s parents refused to join. The following year, most of the members left the cooperative again, and Radošovice entered a forced phase of collectivisation, of which two families of the biggest farmers in the village became victims. Both families had their property confiscated, their fields expropriated and were evicted outside the district. Vladimir Gut’s family was also threatened with eviction, but it did not happen only thanks to the “leniency” of the judge, who did not allow a pregnant mother with three small children to be evicted. The Guts lived under constant pressure, and in 1950, in one of the politically motivated trials, Vladimír Gut’s uncle Alois Kukla was sentenced to twenty years. In 1968, his family’s property was returned to him. They started farming successfully again, but in 1976 their fields were expropriated again. Vladimir trained as a chef-waiter, but was not allowed to study at the agricultural school because of his cadre profile. He returned to farming after the fall of communism in 1990 and has been farming ever since. He is a pioneer of regenerative farming, farming in harmony with nature. In 1989, together with his brother, he founded the Civic Forum in Radošovice and became the first post-Cold War mayor of Radošovice, and remained so in the following election periods. He lives in Radošovice (year 2023), is married and raised two children with his wife.