She was the “voice” of 1968. She was forcibly removed from the radio station

Download image

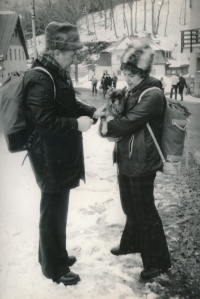

Dagmar Hazdrová was born on 20 December 1933 in the family of Jaroslav Chloupek, an officer in the Czechoslovak army. He was persecuted after the communist coup in 1948 and died shortly after the coup. Dagmar Hazdrová grew up in Chrudim. In 1952 she graduated from the local real grammar school and began studying at a language school in Prague. There she met her future husband Karel Hazdra. Together they moved to Hradec Králové and they both got jobs in the local ČKD. In 1961 she won an audition for a position in the Hradec Králové studio of Czechoslovak Radio. She also worked as a broadcaster there during the August 1968 invasion. Because of her attitudes, she was fired from the radio at the beginning of normalisation and had to earn a living as a cleaner in the town spa and an orderly in the Hradec Králové hospital. In 1975 she moved to Prague with her family. She worked as an accountant before retiring in 1988. In December 1989, she returned to radio and was a programme presenter at the Vltava station. She worked there until 2001. Between 1996 and 2022, her voice was heard on announcements for passengers in transport vehicles throughout the Czech Republic. Dagmar Hazdrová is a widow with two daughters, three grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.