In the GDR we weren’t allowed to talk about the expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia

Download image

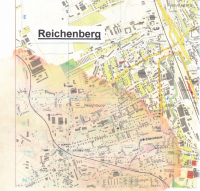

Annelies Hennig, maiden name Weigelt, was born on 2 October 1939 in Jablonec, spending her earliest childhood in Liberec. Her mother Hedwig was from a glass-blowing family from the Jablonec region, her father Richard was a railway worker. After the war Liberec was engulfed in chaos and violence, and on 14 May 1945 her grandmother Anna committed suicide. Shortly afterwards, the rest of the family was forced to leave the house and were interned in a concentration camp, converted from former sports facilities. Several weeks later they were transported in open railway cars to Zittau (Žitava). Her father was originally supposed to remain in the Czech Republic, but after her mother’s nervous breakdown, the family was allowed to remain together. Following her father’s recovery from a typhus infection, he found work with the railways in Weimar, where the family had moved. Their mother’s nervous state had not improved and four or even five times the children to stay at orphanages, as well as with nuns at a monastery. Their grandparents and parents’ siblings were living in West-German Bayreuth, with Annelies visiting them to start with, in 1955 she went to her grandfather’s funeral, but did not have the courage to stay in the West. After primary school she went into training in Carl Zeiss’ Jena optical factory, at eighteen she married the “politically unreliable” circus performer and variety artist Gerolf Hennig. They performed abroad, but only in permitted “Socialist” countries. One of their three daughters married a Polish citizen and moved with him to West Berlin. Ms Annelies met no Sudety Germans in the GDR and did not even talk with her own children about the expulsion of her family from Czechoslovakia, since in the GDR the whole topic of the expulsion of the Germans was taboo. After years of vain attempts, the Hennig family was finally allowed to emigrate to the West in the summer of 1989. After a performance in Nuremberg and various hi-jinks they decided to stay in the FRG and settled down in the Bavarian town of Pegnitz. Meanwhile, their youngest daughter Katrin also headed to the West with her husband and child. Together with hundreds of their compatriots they decided to escape via Prague, where they spent some time in the building of the West-German embassy.