False accusations and removals are easy to make

Download image

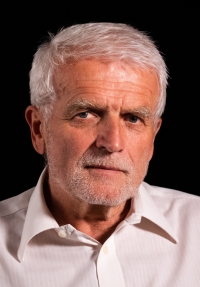

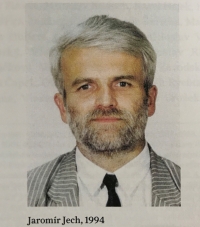

Jaromír Jan Jech was born on 12th August 1949 in Prague and lived in the nearby town of Říčany with his parents. His father, Jaromír Jech, a German and Czech language studies university graduate, worked as a grammar school teacher in Říčany and later became a researcher in the Institute of Etnography and Folklore at the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. After expressing his disapproval with the invasion of the armies of the Warsaw pact into Czechoslovakia, he was dismissed from his job and not allowed to publish. Jaromír Jan graduated from the Říčany grammar school. Between 1967 and 1970 he studied archaeology in Brno. During the invasion of the occupation armies in August 1968 had a summer job for archaeologists in West Germany. He had an opportunity to study in Switzerland at that time but returned to Czechoslovakia. He did not finish his studies and from 1970 worked as an assistant worker in the Léčiva national enterprise in Dolní Měcholupy. In 1988 he became one of the initiators and prime movers of protests against the planned development of a prison in Říčany. This case had not been concluded until after the revolution of 1989. In the revolutionary year of 1989 he joined the activities of the Civic Forum and then participated in local government. He was a mayor of Říčany in 1990-1994. He was then a member of the municipal council in 2002-2010 and a member of the municipal assembly until 2014. He has been an active member of the Union of Towns and Municipalities of the Czech Republic since 1990.