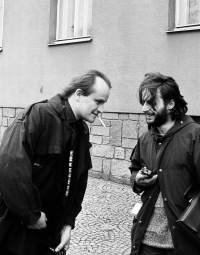

Trapped inside the communist cage, until he lived to see a miracle

Download image

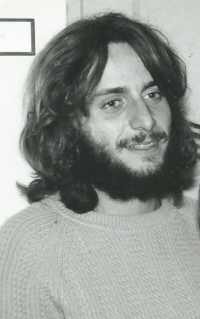

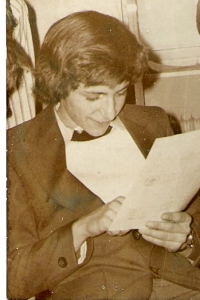

Zdeněk Jeník was born March 10, 1964 in Karviná. Most of his relatives, mainly from mother’s side, were affected by the 1948 communist coup d’état. His father, on the other hand, was a communist but he supported the reforms in 1968 which is why he was fired from his job during the Normalization period. Because he couldn’t find a job, not even as a worker, the family was forced to move to Krnov. The family made no secret of its opposition to the governing regime and at home they listened to foreign broadcasting of the Voice of America and Free Europe. In 1986 Zdeněk attended Jaroslav Seifert’s funeral. He distributed Charter 77 and banned literature by transcribing it. In 1989 he took part in several local demonstrations and was interrogated by the State Security in August 1989. In early November 1989 he visited the Festival of Independent Czechoslovak Culture in Wroclaw where he could see and hear artists in exile live for the first time. He was involved in the Velvet Revolution in Opava. He worked as a journalist after 1989.