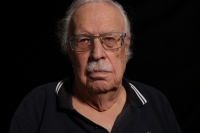

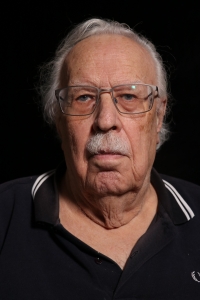

I dug the graves for the victims of the Postoloprty massacre

Download image

Peter Klepsch was born on 10 July 1928 in Žatec (Saaz in German), to the German family of the successful hops trader Alfred Klepsch. At fifteen, in January 1944, he was drafted into the crew of an anti-aircraft (FlaK) gun battery in the Most region. In January the following year he was however arrested, interrogated by the Gestapo and imprisoned for an alleged attempt to help his three friends desert. On the last day of the war he escaped from the prisoner transport and ran home. On 3 June 1945, all the Žatec men were gathered in the town square and force-marched to Postoloprty by soldiers of the Czechoslovak Army. As a previous political prisoner, Peter was assigned to the gravedigger commando and unlike hundreds of his neighbours, he escaped the executions. For several nights he could hear volleys being fired, which he later became convinced were mass executions. He witnessed a number of violent attacks and several murders, both in Žatec and Postoloprty, as well as on the march back to Žatec. He personally buried several victims in the courtyard of the Postoloprty barracks. On 7 June 1945 he was allowed to return to Žatec and after months of forced field labour, in March 1946 he was deported by train through Cheb to Bavaria. In Germany he finished his school, settled down in a region famous for the cultivation of hops and, following in his father’s footsteps, he traded in these till his retirement. Apart from that, he is the author of several popular science books.