Košice, Klatovy, Plzeň, Praha, Jičín – moving across the whole country

Download image

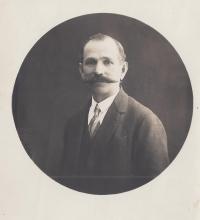

Věra Kordíková, née Hergetová, was born on 19 July 1933 in Košice. Her father Josef Herget was an officer of the Czechoslovak army who had graduated from the Military University in Prague and served at the garrison in Košice. While there he met Ludmila Hynková - they married and had a daughter, Věra. Later they also had a son, Ivan. Following the Munich Agreement and the declaration of autonomy by Slovakia, the Czech soldiers and civil servants had to return to the Czech part of the country. This was also the case of Věra’s father, who was reassigned to Pilsen. His family remained in Spišská Nová Ves for a while. After the German occupation in March 1939, her father was released from the army, and he found an office job at the Upper School of Economivs in Klatovy, where the Herget’s lived during the war. Josef Herget took part in the home resistance movement, he was a member of the resistance group Defence of the Nation. In April and May 1945 he helped the American army, for which he was awarded the Medal of Freedom. In March 1949 he was arrested and interrogated in the Little House (Domeček) in Prague-Hradčany. A military court sentenced him to two years of prison. After his release in Opava they interned him for one more year in a labour camp in Brno. He came home in 1953. In the meantime the Communists had moved his family out of Prague to Jičín, where they lived in a disused dentist’s practice and struggled with financial problems. Věra attended a business academy. After graduating from the school in 1952 she worked briefly in Hradec Králové and then at Agrostroj Jičín. She married and moved to Vrchlabí, where she gave birth to a daughter. In 1966 she moved to Pilsen, where her parents lived. She settled down in the West Bohemian metropolis. She found employment at ČSAO, where she worked until her retirement in 1989.