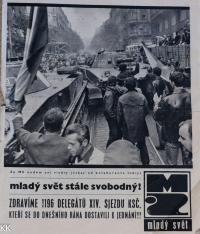

“Planes boomed throughout the night, and in the morning the tanks arrived.”

Download image

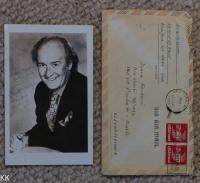

Jan Kovanic was born in Liberec on the 14th of May 1951. His parents divorced when he was five. On the 21st of August 1968, he was in Liberec when the armies of the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia. The following year he graduated from the Liberec grammar school. He was greatly affected by Jan Palach’s act of protest [a young student, who set fire to himself in January 1969 - trans.]. Jan Kovanic went on to study at the Faculty of Electrotechnics of the Czech Technical University. He worked as a design engineer, later as an energy specialist at Czech Telecom. He married and settled down in Prague, where his wife bore a daughter in 1976 and a son three years later. In the years 1988-1989 he took part in demonstrations against the regime, in June 1989 he signed the declaration Několik vět [Several sentences], in August 1989 he published texts in the Bulletin of the Movement for Civic Freedom (MCF). Around the 21st of August 1989, he provided temporary shelter in his flat for Rudolf Battěk. Within the MCF, he and his wife initiated a separate list of candidates for the MCF, which was open to all independent candidates - but without much success. After November 1989, he sold books, later he began to publish himself. From 1997 he is a regular writer for the internet daily Neviditelný pes [Invisible Dog, the first Czech internet daily, with significant readership - trans.] - under the heading Šamanovo doupě [Shaman’s Lair], later adding his own blog; synchronically with texts published in other media, he has written approx. 2,000 articles. In 2013, his wife died, but instead of breaking down, he continued his frantic activity.