I was terribly confused inside, something was wrong. I understood that man was worthless

Download image

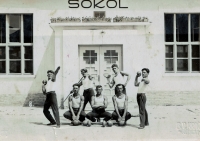

Karel Kuchynka was born on 17 May 1934 v Nové Strašecí as the youngest of three children. It is highly probable that his father, Richard Kuchynka, was a member of a number of anti-Nazi resistance groups, though nobody talked about it, and he became an obvious model for his sons. Karel Kuchynka already at a very early age tried to help. Starting in autumn 1944 until the end of the war they hid a group of Soviet prisoners of war who managed to escape from a work camp in North Bohemia. It was the crew of a captured submarine, including its captain, who at the end of the war would go to be arrested by members of the Stalinist counter-intelligence group SMERSH. As a captured officer he was considered a traitor and, after his arrest, was certainly executed. Ten-year-old Karel Kuchynka during the war was a witness of many drastic events in the surroundings of Nové Strašecí. Whether it was the Nazi persecution against Czech resistance fighters, the results of the air raids at the end of the war, the Nazis’ actions toward the Soviet prisoners of war, but just as well the actions of Czechs toward the Germans. In the 1950s he married Jarmila Hajná, the daughter of a villager from the town of Řevničov na Rakovnicku. Her father, Rudolf Hajný, during the time of collectivization, was labeled a kulak, was persecuted, and the family ended up in social isolation. Meanwhile, Karel Kuchynka fulfilled his mandatory military service which he served as an electrician in the army unit Border Guard in the Aš salient. He has many memories of the functioning of these units as well as life along the Iron Curtain. For his entire life he stood against manifestations of injustice and oppression and tried to live according to his conscience. He is a widower and has two children. He lives (2020) in the town of Hyršov, not far from Všeruby.