So that the building effort of the working people shall no longer be disrupted

Download image

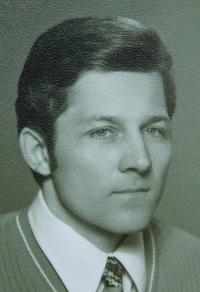

Vladimír Lakva was born on June 20, 1942 in Bohuňovice near Olomouc as the only child of Vladimír and Marie Lakva. During the process of collectivization of farms, which was directed by the communist regime, Vladimír’s father kept refusing to join the Unified Agricultural Cooperative (JZD). He was thus marked as a kulak and with the help of a police informer he was sentenced for high treason in a staged court trial to nineteen years of imprisonment and confiscation of property in 1953. His wife and ten year old Vladimír were subsequently evicted from their home and relocated to Lindava three hundred kilometres away. Vladimír Lakva Sr.’s brother, who was blind, was forcibly sent to an institution, and his sick mother was sent to an old people’s home, where she died half a year later. The villagers’ resistance was put down and the Unified Agricultural Cooperative was established shortly after. Its former opponents eventually joined as well because of fear. Little Vladimír and his mother were allowed to move in with her parents in Lašťany near Bohuňovice half a year later and after the presidential amnesty in 1960 Vladimír’s father was released from prison as well, although he was a psychically broken man. In 1965 the authorities allowed the family to return to their farm, which had been devastated by the twelve years when it was used by the JZD. However, all of them were forced to start working in the local JZD. Vladimír’s parents were assigned to work as cow feeders, which was a physically demanding and time consuming work, and Vladimír was sent to the cooperative’s workshop. He remained working there for ten years before transferring to a logging company in Bohuňovice for health reasons. He eventually kept working there until his retirement. In 1965 he married Ludmila Vychodilová and later they had son Vladimír and daughter Irena. Only his mother lived long enough to see the fall of the communist regime and family’s rehabilitation. Vladimír’s father died in August 1981.