At first they didn’t believe there would be a nuke

Download image

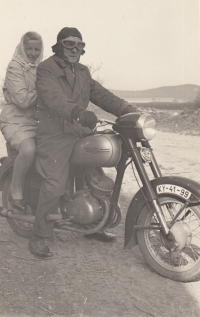

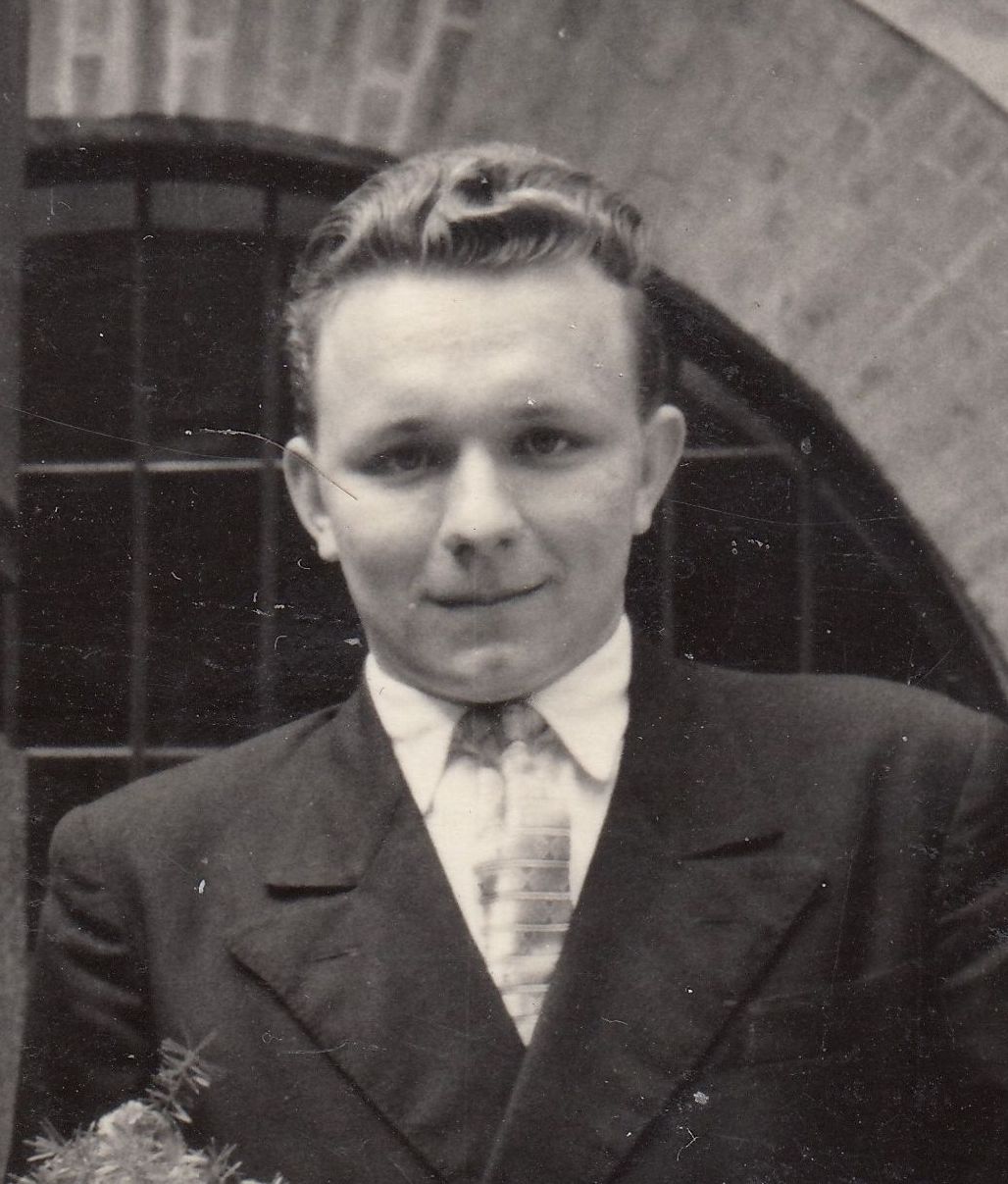

Josef Lexa was born as an only child on 31 March 1936 to Josef and Růžena Lexa. The family owned a small farm (6 ha) in the village of Temelínec, now a defunct village. The Lexa farm flourished. During the war they secretly supplied food to relatives in České Budějovice and Týn nad Vltavou. In May 1945, the witness witnessed the dramatic end of the war in Temelín. His parents were not members of the Communist Party. When the JZD (Unified agriculture cooperative) in Temelínec was started in the early 1950s, father did not want to join the cooperative. He was one of the last to apply under pressure. After graduating from the secondary school in Týn, he entered the Czech Technical University, but he was not interested in studying geodesy. After a year he transferred to the agricultural college, which he graduated from in 1960. During his studies he joined the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. After the war, he started working at the agricultural department of the Agricultural Inspectorate in České Budějovice. As an agricultural economist, he managed first the JZD and then the state farms (Hluboká nad Vltavou, České Budějovice, Nové Hrady and Trhové Sviny). He describes in detail the state of Czechoslovak agriculture in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1968 he signed the Two Thousand Words manifesto, for which he was later expelled from the Communist Party. He could have stayed at the ONV (Regional National Committee), but it was a future without the possibility of any career advancement. When the construction of the Temelín Nuclear Power Plant (JETE) began in the 1980s, Růžena and Josef Lex had to move out of Temelín. Their house was later razed to the ground. After 1989, he became the director of the České Budějovice branch of the Czech Statistical Office. All democratic elections were held under his supervision until his retirement in 2000. Josef Lexa lived in 2024 in Nové Hodějovice near České Budějovice.